I’m pleased to co-author a new study released today by the Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) at UC Berkeley Law that identifies the primary factors underlying cost and schedule overruns for rail transit construction and presents policy recommendations to overcome key barriers.

Improving rail transit delivery is critical for meeting climate and equity goals, given that the transportation sector contributes the majority of the state’s total greenhouse gas emissions. Since the bulk of these emissions come from private automobile travel, rail transit—from heavy-rail subways to overhead-powered trolleys—offers low-emission and low-cost commuting and travel options across income levels.

However, in California and throughout the United States, rail transit infrastructure projects have long suffered from cost overruns and deployment delays that reduce the value of investment and erode public trust. These state and nation-wide projects lag international peers.

For example, completed U.S. heavy rail projects (with trains powered from below via an electric “third rail”) cost more than twice as much on average than their European, Canadian, and Australian counterparts, while U.S. light rail projects (powered by overhead electric lines) cost around 15 percent more than similar projects in Europe, Canada, and Australia. In the United States, different governance authorities hold veto power over multiple decision points, and lack of alignment between these authorities can derail regionally-crucial projects.

Some of the largest and highest-profile California projects, such as the second phase of the Silicon Valley Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) extension into San José, are particularly slow and expensive. How can California deliver high-quality rail transit projects while keeping on budget and on schedule? Although transit ridership has fallen during the COVID-19 pandemic, ridership is beginning to rebound and transit agencies are committing billions to new infrastructure.

With funding from California SB 1 research dollars through the UC Berkeley Institute of Transportation Studies, CLEE analyzed national and international construction trends and assessed five California rail case studies that offer examples of delivery issues and methods to address them. Common challenges included lack of megaproject management capacity and expertise; project design and scope creep; lack of agency coordination; inefficient procurement and contracting methods; and need for excessive stakeholder outreach.

The five case studies included rail transit projects in Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, and San José, as well as California’s statewide high-speed rail project (which is not a traditional intracity rail line but will be vital to state efforts to reduce vehicle travel). Drawing on the lessons learned from these five cases, CLEE recommends state, regional and local transit leaders consider:

- Forming regional collaboratives to house permanent expertise not tied to any individual local project, with staff available to consult with or contract out to projects when needed. Such a collaborative could benefit projects like the Bay Area Rapid Transit Berryessa Extension, where multi-agency oversight of different project elements required dedicated coordination and communication.

- Creating a statewide office to provide dedicated staff support/ technical assistance to facilitate coordination among local and regional agencies or offer additional funding to agencies that provide detailed plans for addressing any in-house staffing needs, as applicable. For example, the San Francisco Central Subway involved complex construction in a high-density residential and commercial district with significant overruns and delays, in part because agency staff had less megaproject experience than contractor teams. California High-Speed Rail similarly struggled with sufficient in-house capacity, particularly during its early stages.

- Using project procurement and delivery methods that includes early contractor involvement to ensure the total cost of building expensive projects in dense, complex areas is identified before construction begins. For example, the San Diego Mid-Coast Corridor Trolley successfully utilized the construction manager/general contractor or construction manager-at-risk contracting method (CMGC/CMAR), in which the project owner engages a designer and a construction manager separately during the design phase, and the owner and construction manager negotiate a guaranteed maximum price for construction prior to design completion before starting the build phase. This method helped ensure that this relatively pricey project stayed on budget.

- Legislatively granting master permitting authority to transit agencies with priority rail transit projects (including engineering, street closure, and similar project completion-critical permits) to reduce delays and costs imposed by local governments or large or powerful stakeholders along the route. For example, Los Angeles Purple Line Section 1 leaders coordinated with local governments to align expectations about restricted construction times and locations, as local governments held permitting authority over the transit agency.

- Avoiding the addition of significant, non-essential betterments and limiting bespoke design for extraneous station elements (e.g., complex facades), particularly after the design stage. Multiple case study projects suffered from expensive, over-designed project elements to appease stakeholders along the route with effective veto power and other leverage. Determining who will pay for these modifications is a crucial decision point that can push a transit project over budget and behind schedule, if not appropriately managed. State and federal leaders could condition funding on avoiding outcomes that delay a project or place unreasonable cost expectations on the agency and its contractors.

You can read the full report as well as a short policy brief.

Register for a free webinar on Thursday, January 27 at 10:00am Pacific time to learn about the report’s top findings with an expert panel including:

- Hasan Ikhrata, Executive Director of the San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG)

- Brian Kelly, CEO of the California High-Speed Rail Authority

- Therese McMillan, Executive Director of the Metropolitan Transportation Commission

Thanks to my report co-authors Katie Segal, Ted Lamm and Michael Maroulis.

ABC7 News in Los Angeles explored the history of the now-defunct Los Angeles streetcar system, featuring an interview with yours truly.

The piece from reporter Olivia Smith describes how the Pacific Electric Red and Yellow Car electric trolleys shaped development patterns in L.A. at the turn of the last century. It also debunks the myth that car companies destroyed the system.

The modern Los Angeles rail network is now built on some of the old rail rights-of-way from the system, as I discussed in my 2014 book Railtown.

On tonight’s State of the Bay we’ll discuss the recent crisis in Afghanistan, including how Bay Area residents are impacted and finding ways to help. Joining us will be Congressman Eric Swalwell, Representative of California’s 15th district; Aisha Wahab, Hayward City Council Member and Board Member with the Afghan Coalition; and Robert Crews, Professor of History at Stanford University and a leading scholar on Afghanistan.

Plus, we’ll look at the State of the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (Muni) with its Director of Transportation, Jeffrey Tumlin.

And finally we’ll get an inside look at the California Academy of Sciences when Joseph Pace interviews Elizabeth Babcock, the organization’s Dean of Education.

Tune in tonight at 6pm PT on KALW 91.7 FM in the San Francisco Bay Area or stream live.

What would you like to ask our guests? Post a comment, tweet us @StateofBay or send an email or voicemail to StateofBay@gmail.com. You can call 866-798-TALK with questions during the show!

President Biden is nearing a potentially significant bipartisan win on federal infrastructure spending, as a $550 billion package nears approval in the United States Senate. But the United States has a poor track record of spending this kind of money wisely, particularly on rail transit.

As the Eno Center has documented, U.S. taxpayers pay a premium of nearly 50 percent on a per-mile basis to build rail transit compared to our global peers. Tunneled projects furthermore take nearly a year and a half longer to build than abroad

In a piece I just published for Smerconish.com, I lay out key requirements that federal leaders should consider including as conditions on these “Biden bucks” to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past. To summarize the piece, federal transit dollars should:

- Include measures that prevent local transit agencies from “over-designing” projects to appease narrow interests with counter-productive and costly concessions;

- Ensure local leaders choose optimal rail transit routes to boost ridership and overall utility and cost-effectiveness;

- Streamline federal permitting, including via multi-agency coordination and expedited environmental reviews, with exemptions from analysis on impacts not all that relevant to environmentally beneficial rail – like traffic, air quality, and noise;

- Incentivize smart procurement of contractors, including a maximum on contract size to break up the work on large projects among smaller and more competitive firms;

- Give transit agency staff more flexibility on construction oversight, including ability to make basic decisions on project implementation to speed construction; and

- Require 24/7 construction to shave potentially years off construction timelines.

With a challenge this complex, no single solution will cure the United States of its poor track record on rail transit project delivery. But the infrastructure bill now gives Congress and the Biden Administration an opportunity to start fixing the problem — delivering climate-friendly infrastructure quickly and effectively to more people.

Dr. Martin Wachs, who passed away Sunday evening, was California’s preeminent transportation scholar. He knew both Northern and Southern California well, having joined UCLA’s urban planning department in 1971 and founded its Institute of Transportation Studies, while also spending a decade at UC Berkeley in the interim, where he chaired that’s schools transportation studies program. Much of our knowledge about the history of the state’s transportation system and our ability to evaluate its efficacy comes from his prolific scholarship and role as a public commenter on major transportation decisions.

But more than that, he was a humble and generous person with boundless curiosity and intellect. I first met him when I was researching the history of the Los Angeles Metro Rail system, back in 2007. His influence on Los Angeles transit debates was all over the archival and media documents I found from the 1970s and 1980s, from his scholarship to his op-eds to his conference appearances. Los Angeles elected leaders took his research seriously, even if they didn’t like his skepticism about rail transit in a city as spread out as Los Angeles.

I had originally approached the book as a rail enthusiast, and when I met him in his then-RAND office a few blocks from my Santa Monica apartment, he seemed aghast that I would set out to write a book that would promote rail. But he nonetheless provided me with contact information for a former student who had researched Metro Rail history, along with a few large binders of research for my files. I thanked him profusely and relied on his research for much of the discussion in the book on L.A.’s rail history. In fact, much of what we know about the demise of the Pacific Electric streetcar system in Southern California and its myth-busting conclusion that it was not a car company conspiracy is due to his groundbreaking research.

When my book Railtown was finally published seven years later in 2014, Marty was invited to co-present with me on its findings at an event at UC Berkeley. Top faculty at the school lined up to greet him, like fans seeking autographs at a celebrity book signing. It was an impressive indication of his impact and role as a longtime mentor and generous colleague to so many of them. He was like a returning rock star in his field.

While I was a bit worried how he would react to the book, his comments that evening were thoughtful and ultimately complimentary. I chronicled them at the time on this blog. They are worth reading for anyone interested in his take on rail. What stood out to me was his comment that the book showed him how little politicians actually heeded the advice of transportation scholars, as they forged a path for rail investments despite the caution of experts. And as a recent member of the high speed rail peer advisory group, he was finding a similar dynamic at play, with politicians making short-sighted decisions on this crucial California infrastructure project that have come back to haunt and potentially torpedo its progress.

After that evening in 2014, we kept in touch, even co-authoring an article series on the pros and cons of rail transit investments. If I ever had any questions or needed advice or resources, Marty would jump at the chance, providing thoughtful responses, lists of resources to review, and people to contact. Hundreds of others could say the same thing — his legions of former students now working on urban planning issues, his colleagues, and countless leaders and readers who have benefited from his scholarship and thinking on these complicated issues. You can read some of their tributes (and find out how to honor his memory) on this UCLA website.

Just a few months ago I contacted him about a new rail transit study we’re conducting at UC Berkeley Law. Typical Marty, he immediately offered to schedule a Zoom with our team, providing invaluable advice. But what I remember now is his initial email back to me, where he reflected on his life during the pandemic times. Like most of us, he was home-bound, and he missed his children and grandkids. But he was enjoying his work (including a manuscript in progress that I hope will be finished somehow) and took solace in his garden.

I pictured him in the warm Southern California sun tending to his plants and wonder now who will care for them with his absence? It’s just a small example of the giant hole his death leaves in our world. But Marty’s amazing legacy — beyond the scholarship and influence on public debates — includes his many former students, colleagues, and friends. He trained and supported so many well, who can do their best now to carry on the work he advanced, on issues that affect so many people’s daily lives.

Rest in peace, Marty, and thank you.

President Biden yesterday unveiled his “infrastructure” plan, but it’s really his best and greatest shot to address climate change. I’ll be speaking about the plan and what it means for the climate at 10:20am PT on KQED’s Forum. You can also hear my thoughts on the electric vehicle charging aspect of the plan on yesterday’s NPR Marketplace.

The proposal calls for transformational investments in rail, bridges, and road repair, along with a decarbonized electricity grid, incentives for electric vehicles, an end to fossil fuel subsidies, and home energy retrofits, among other goals. The plan even seeks to end single-family zoning.

Tune in this morning to hear more!

If you’re interested in the past, present and future of rail transit in Los Angeles, check out the video above from my talk this week with Streets For All. My moderated comments begin about 20 minutes in. We covered everything from the dismantling of the Los Angeles streetcar network to delays building current rail lines to whether anyone alive today will ever get to ride high speed rail.

And if you don’t know Streets For All, they’re a volunteer-based organization advocating for equitable redesign of streets and the transportation network to favor transit, walking and biking, as a climate change and quality-of-life necessity in Los Angeles.

Consider becoming a member if you’re interested in these issues. I thank them for hosting me for this talk!

With the presidential election over, Joe Biden faces a U.S. Senate that still hangs in the balance. But even with a Democratic runoff sweep in Georgia next month, it will be very divided. So what will be possible for a President Biden and his administration to achieve on climate change?

Agency action, foreign policy changes, and spending can all make a difference on emissions, with any COVID stimulus and budget deals with Congress, if feasible, providing potential avenues for further climate action. Here are some ideas along those lines, broken out by key sectors of the economy.

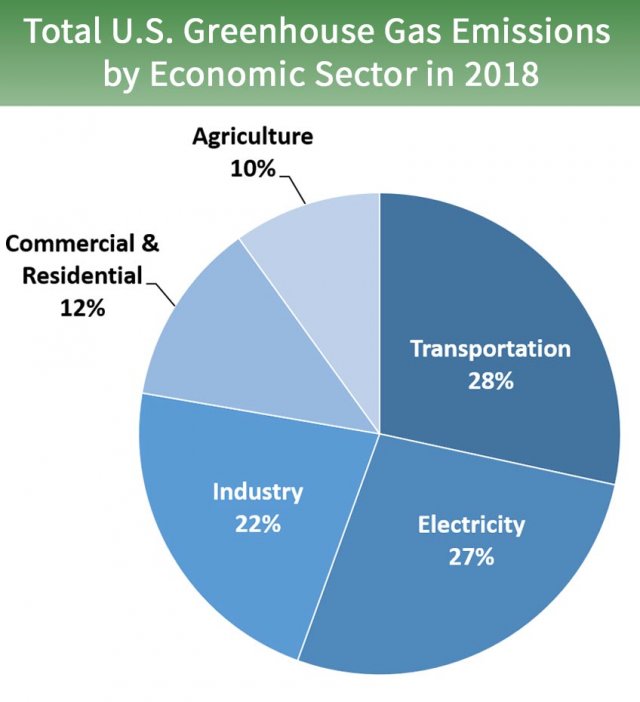

Action on Transportation

As the EPA chart above of 2018 emissions shows, transportation contributes the largest share of nationwide greenhouse gas emissions at 28%. The best way to reduce those emissions is to decrease per capita driving miles through boosting transit and the construction of housing near it, as well as switch to zero-emission vehicles, primarily battery electrics.

Transit-oriented housing is largely governed by local governments, who generally resist construction. Absent state intervention or federal legislation from a divided Congress, the Biden administration will have to make surgical regulatory changes directing more grant funds to infill housing and potentially use litigation and other enforcement tools to prevent and compensate for racially discriminatory home lending and racially exclusive local zoning and permitting practices.

On transit, a Biden administration would be very pro-rail, especially given the President-elect’s daily commuting on Amtrak in his Senate days. If the Senate flips to the Democrats, high speed rail could be a big part of any bipartisan COVID stimulus package, if it happens, which would be a lifeline to the California project that is otherwise running out of money. Other urban rail transit systems could benefit as well, and the U.S. Department of Transportation could favor and streamline grants for transit over automobile infrastructure. Notably, LA Metro CEO Phil Washington, responsible for implementing the nation’s most ambitious rail transit investment program in Los Angeles County, is chairing Biden’s transition team on transportation.

On zero-emission vehicles, Biden may have relatively strong tools to improve deployment of this critical clean technology. First, perhaps through a budget agreement with Congress, he could reinstate and extend tax credits for zero-emission vehicle purchases, which have expired for major American automakers like General Motors and Tesla. Second, he could use the enormous purchasing power of the federal government to buy zero-emission vehicle fleets. And perhaps most importantly to California, his EPA can rescind its ill-conceived attempt at a fuel economy rollback for passenger vehicles and then grant the state a waiver under the Clean Air Act to institute even more stringent state-based standards, toward Governor Newsom’s new goal of phasing out sales of new internal combustion engines by 2035.

Reducing Electricity Emissions

The electricity sectors comes in a close second place, with 27% of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions. The move toward renewable energy, particularly solar PV and wind turbines, is so strong that even Trump had difficulty slowing it down during his single term in office, in order to favor his fossil fuel supporters. But nonetheless, the Trump administration created some strong headwinds which can now be reversed.

First and foremost, President-elect Biden can drop the tariffs on foreign solar manufacturers, which drove up prices for installation here in the United States. Second, as with the zero-emission vehicle tax credits, a budget deal with Congress could bolster the federal investment tax credit for solar, which steps down from the initial 30% toward an eventual phaseout for residential properties and 10% for commercial properties. The credit could also be extended to standalone energy storage technologies, like batteries and flywheels, if Biden budget negotiators play their hands well (easy for me to say). A Biden administration could also improve energy efficiency by dropping weak regulations on light bulbs and appliances like dishwashers at the U.S. Department of Energy and introducing more stringent ones instead.

Legislatively, any COVID stimulus deal (again, if it happens) could potentially contain money for a big renewable energy buildout, including for new transmission lines, grid upgrades, and technology deployment. In terms of regulations, if Biden is able to get any appointments through the Senate to agencies like the Federal Regulatory Energy Commission (FERC), that agency could make climate progress by simply letting states deploy more renewables and clean tech, including demand response, as well as potentially supporting state-based carbon prices (a move supported by Trump’s FERC appointee Neil Chatterjee, which promptly resulted in his demotion last week).

Slowing Fossil Fuel Production

The two big moves for the Biden administration will be to stop new leases for oil and gas production on public lands (including immediately restoring the Bear’s Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments) and bringing back the methane regulations on oil and gas producers that the Trump administration rolled back. As a bonus, his Interior Department could engage in smart planning to deploy more renewable energy on public lands, where appropriate, including offshore wind.

Other Climate Action

The list goes on for how the Biden administration can embed smart climate policy into all agencies and facets of government, with or without Congress. Of particular note, his appointees at financial agencies like the Federal Reserve and U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission could bolster and require climate risk disclosures for institutional and private investors. The U.S. Office of Management and Budget could ramp back up, based on the best science and economics, the social cost of carbon, which represents the cost in today’s dollars of the harm of emitting a ton of carbon dioxide equivalent gas into the atmosphere. This measure provides much of the economic justification for the federal government’s climate regulations. And of course, President-elect Biden can have the U.S. rejoin the 2015 Paris climate agreement immediately upon being sworn in (though the country will need to set a new national target).

Overall, Biden’s win means the U.S. will regain some climate leadership at the highest levels, with much that can be done through congressional negotiations, agency action, and spending. However, the stalemate in the US Senate likely means that any hopes for big new climate legislation will be dashed. As a result, continued aggressive action at the state and local level, as well as among the business community, will be critical to continue to help push the technologies and practices needed into widespread, cost-effective deployment to bring down the country’s greenhouse gas footprint.

One election certainly won’t solve climate change, and the costs continue to rise to address the impacts we’re already seeing from extreme weather. But given the current political climate, the actions described above could allow the U.S. to still make meaningful progress to reduce emissions over the next four years and beyond, even in an era of divided government.

Back in 2017, many breathless legal observers (including me) thought that the California Supreme Court had just opened up a major loophole in Prop 13/Prop 218 restrictions on raising local taxes. The two voter-enacted amendments to the state constitution otherwise require that any new taxes receive a two-thirds vote to go into effect.

But the Court ruled that year in California Cannabis Coalition vs. City of Upland that the supermajority hurdle did not apply to taxes put on the ballot through citizen petitions. Some legal experts and advocates pushed back on how much of a loophole the decision opened, suggesting that the case was overblown.

Now today we have confirmation that in fact the Supreme Court did dramatically scale back the two-thirds hurdle that has stymied local revenue measures.

The case at issue arose in San Francisco, where Proposition C passed by a majority, but not two-thirds, to fund homeless services through a new corporate tax. The measure was placed on the ballot by a citizen petition, so the city attorney had determined that only a simple majority was needed, based on the 2017 decision.

The Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association sued, lost and appealed, but yesterday the California Supreme Court declined to review. So barring any new cases or contrary appellate court rulings on this same issue, the case is closed, so to speak. That is, unless the voters approve a new restriction to close this loophole, as Prop 218 was originally placed on the ballot to close previous loopholes in Prop 13 based on an earlier California Supreme Court decision.

The ramifications? Any local government that wants to raise revenue for purposes like new transit or wildfire prevention could theoretically ask a nonprofit or business group to conduct signature gathering to place the measure on the ballot. Then they would only need a simple majority approval at the ballot box. In short, as I wrote back in 2017, this decision could be transformational for local “self-help” efforts to fund badly needed infrastructure projects and services.

Housing policy is at the center of all of our major societal problems in the United States:

- Care about racial justice? Restrictive housing and land use policies are responsible for our deeply segregated towns and cities.

- Climate change? Bad housing policies are the reason why so many people are forced into long, emission-spewing commutes, because they can’t afford to live close to their jobs.

- Economic inequality? Inflated home prices and rents increasingly force middle- and low-income residents into low-opportunity areas, while shutting them out of the wealth-generating possibilities of home ownership. Just to name a few issues affected by housing.

So why can’t we address the high cost of housing, particularly near transit and jobs? There are two culprits: high-income homeowners who support exclusionary local land use policies that restrict housing supply, which prevents others from moving into their communities and deprives them of the educational and economic opportunities that come with living in these areas. Second, the state and federal government is unwilling to provide sufficient public subsidies for affordable housing (though the scale of the need at this point is simply massive, especially given the country’s inability to build housing at a reasonable price).

Perhaps with these dynamics in mind, then-Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom campaigned for governor in 2018, promising 3.5 million new housing units to address the state’s severe housing shortfall. But after two legislative sessions, the Governor so far has no meaningful legislative accomplishments on increasing housing production. Like 2019, this just-concluded 2020 legislative session proved to be a bust (yes, Covid-19 interfered, but housing was one of the few remaining priorities that the legislature was committed to addressing this year).

Here are the gory details of the housing bills from the original legislative “housing package” in January that did not survive:

Assembly defeats:

- AB 1279 (Bloom): would have identified high-resource areas with strong indicators of exclusionary patterns and require zoning overrides to encourage production of small-scale market-rate housing projects and larger-scale mixed-income affordable projects.

- AB 2323 (Friedman): would have expanded CEQA infill exemptions to projects in low-vehicle miles traveled (VMT) areas.

- AB 3040 (Chiu): would have incentivized cities to upzone to allow for fourplexes in neighborhoods currently zoned solely for single-family housing.

- AB 3107 (Bloom): would have allowed streamlined rezoning of commercial land for housing.

- AB 3279 (Friedman): would have amended administrative and judicial review for various projects under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

Senate defeats:

- SB 899 (Wiener): would have streamlined review for religious institutions seeking to build housing on their property.

- SB 902 (Wiener): would have streamlined approval for up to 10 housing units per parcel near transit.

- SB 995 (Atkins): would have fast-tracked CEQA review for environmentally beneficial infill projects.

- SB 1085 (Skinner): would have expanded density bonus law by allowing rental housing developers to increase the size of their projects 35% if at least 20% of the units were moderately priced (rent at 30% below market rate for the area).

- SB 1120 (Atkins): would have allowed two homes on every property zoned for single-family homes in California; would have also allowed single-family properties to be split into two lots.

- SB 1385 (Caballero): would have made it easier to rezone commercial land for housing and streamline approval for projects on that land.

- SB 1410 (Caballero): would have provided rental relief through tax credits to landlords to fill unpaid rent.

It’s also worth reiterating that the senate voted down in January an amended version of Senate Bill 50 (Wiener), which would have reduced local restrictions on apartments near major transit and jobs.

And strangely, SB 995, SB 1085, and SB 1120 all passed the Assembly at the last minute, but Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon scheduled the vote too late for a concurrence vote in the Senate. As a result, the bills died.

But the news was not all bad. Some housing bills did pass, including:

- AB 725 (Wicks): requires that no more than 75 percent of a city’s regionally assigned above-moderate income housing quota can be accommodated by zoning exclusively for single-family homes, with the remainder on sites with at least 4 units.

- AB 1851 (Wicks): requires local governments to approve a faith-based organization’s request to build affordable housing on their lots and allows faith-based organizations to reduce or eliminate parking requirements.

- AB 2345 (Gonzalez): increases the density bonus and the number of incentives available for a qualifying housing project.

- SB 288 (Wiener): temporarily exempts from CEQA review infill projects like bike lanes, transit, bus-only lanes, EV charging, and local actions to reduce parking minimums, among others, until 2023 (disclosure: I helped Assemblymember Laura Friedman and Assembly Natural Resources Committee chief consultant Lawrence Lingbloom draft the parking provision, along with Mott Smith of the Council of Infill Builders).

So there we have it in 2020. A few successes, but mostly a wipeout. Perhaps recognizing the urgency after two failed sessions, Governor Newsom appeared this week to offer something of a belated endorsement of SB 50 and SB 1120, two of the more consequential bills that failed in the legislature this year:

But absent strong leadership from the Governor’s office and legislative leaders, this pattern of failure on housing production will likely continue, exacerbating all the challenges I discussed above that are affected by dysfunctional housing policy. That means we can expect worsening racial injustice and segregation, greenhouse gas emissions, and economic inequality, to name just a few, until the state can finally, meaningfully address this problem.