Major League Baseball just announced that the season will be delayed, due to an owner lockout. And most Americans just shrug. The sad fact is that the sport that used to be America’s pastime has seen audience interest decline significantly over the past few decades.

The signs are everywhere: ticket sales have been declining for two decades, and even the World Series hardly draws an audience (viewership declined from 20% of Americans in the 1970s to just 3 percent by 2020). The fanbase is also older and whiter, with an average age now 57, up from 52 less than twenty years ago, with hemorrhaged appeal to Black Americans in particular.

And it’s all the fault of my hometown team: the Oakland A’s. The A’s are the team that pioneered how to hack the rules of the game using then-emerging big data tools, made famous in the 2002 Michael Lewis book Moneyball. The result has been a far slower, less dynamic, and boring game.

As the New York Times detailed, last season saw the longest average game time in history (3 hours 11 minutes), along with the most pitchers used per team (4.43 per game, tied with 2020). Worse, it now takes an average of four minutes between balls put in play. Meanwhile, teams averaged nearly nine strikeouts per game, while stolen bases (0.46 per game) have decreased to a 50-year low.

This is not the way the game was originally played, or even how the game is played in Little League through high school still today.

So what happened? In short, the game has been hacked by Big Data, led by the A’s.

Using complex data formulas, teams have figured out optimal pitching matchups for virtually every batter, leading to relentless and time-consuming pitching changes. Pitchers are now coached and conditioned to throw faster and hit specific, computer-prompted spots, leading to injuries and more strikeouts.

Hitters meanwhile use complex computer analyses of swings to focus on “launch angles” to maximize home runs, even as strikeouts skyrocket. And nobody steals bases anymore, as the data show that is inefficient to do.

Defensively, teams have used algorithms to determine the optimal “shift,” stacking all fielders in the area where hitters are most likely to hit. As a result, screaming liners that use to go for base hits or doubles instead disappear regularly into well-positioned mitts in shallow left or right field.

In short, all the things fans come to see and love about the game are gone: the crack of the bat, great defensive plays, cat-and-mouse games on the basepaths, and dominating pitching performances. Games drag on with little action other than walks and home runs.

And the decline of the game is only going to get worse, due to the rise of other entertainment options like video games, as well as demographic change in the United States that might favor other sports like soccer (interestingly, sports like football and basketball don’t seem to have a worse product due to big data, perhaps due to the contrast with baseball’s more precision-based style of play).

So how can the game fix itself? The current proposals are designed to triage the problems. There’s talk of banning the defensive shift, moving the pitchers mound back to give hitters more time to swing, forcing a pitcher to stay on the mound for a minimum number of batters, and limiting the time between pitches or batting changes, among others.

But these are just cosmetic changes chasing the data revolution. They don’t get to the heart of the problem. Instead, there’s one fix that could solve much of the problem plaguing baseball.

It’s simple: expand the strike zone, and do so dramatically.

With a bigger strike zone, hitters couldn’t be so selective, waiting on a “meat” pitch to belt or trying to work a walk. They would have to put the bat on the ball, generating action, movement, and defensive plays. They also would be less likely to hit into the defensive shift, as they’d have to be more agile to hit pitches farther out of their comfort zone.

That increased hitting would in turn reduce pitch counts and the need for time-wasting pitching changes. In short, you’d see more defense, more action, and shorter games. That’s the game that many of us came to love as children, including me when I fell in love with the Oakland A’s back in the 1980s.

I’m sure there are myriad reasons this change would be tough to implement. Players might push back. Owners may balk.

But unless something drastic is done, the national pastime risks fading into obscurity. Like any failing industry or business, a revamp is needed. Expand the strike zone, or watch the sport wither like many others before it.

Baseball fans don’t like bad balls-and-strikes calls from home plate umpires. But rather than yelling at the ump, maybe they should look at their own tailpipe.

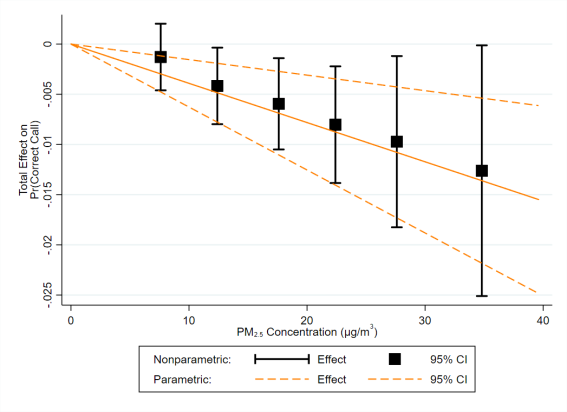

As UC Berkeley colleague Meredith Fowlie describes from a new study by James Archsmith (University of Maryland, College Park), Anthony Heyes (University of Ottawa), and Soodeh Saberian (University of Ottawa), bad air quality may be to blame for bad calls:

To sum up, these authors use publicly available data to estimate a causal relationship between air pollution exposure and umpire performance (measured as the share of umpire calls that agree with the computer-based assessment). After controlling for all sorts of factors that could affect an umpire’s judgement (such as venue, day-of-week, temperature, humidity, wind speed, pitch break angle, pitch type, etc.), they find a significant relationship between air pollution and on-the-job error rates:

People typically associate bad air quality with public health challenges, like increased respiratory ailments and premature death. But this study shows in stark terms how overall job performance decreases with increasing pollution.

And just look at the populations most likely to live in polluted areas, as the San Francisco Chronicle recently reported based on a new state study:

A new report released by the state Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, a scientific arm of California’s Environmental Protection Agency, documents what environmental justice advocates have been saying for years — the racial makeup of communities suffering the worst environmental degradation in California are disproportionately Latino and African American.

…

Nearly 1 in every 3 Latinos and African Americans lives in the top 20 percent of most pollution-impacted communities. Only 1 in 14 whites calls these places home.

It’s one thing for these communities to face the historical disadvantages of discrimination and modern-day racism. But pollution as well presents an unjust and counter-productive barrier to achievement.

On that score, the State of California is striking out as much as home plate umpires at smoggy baseball games.

Rendering of proposed gondola to Dodgers Stadium

Who knew gondolas and baseball games could be a thing? But now we have two major league baseball teams — the Oakland A’s and Los Angeles Dodgers — exploring options to build gondolas to ferry fans from rail transit stations to the park.

As Jenna Chandler at Curbed L.A. reported, the Dodgers are working with a private company to submit plans for an “aerial tram” to link the major transit and train hub of Union Station near Downtown L.A. across the freeway to Dodgers Stadium in Chavez Ravine.

The project is estimated to cost $125 million and would be privately funded, with unclear support required from L.A. Metro to provide procedural assistance and right-of-way selection. The tram could potentially be operational by 2022.

Meanwhile, the Oakland A’s hope a gondola could solve the transportation challenges at one of their best remaining sites for a new ballpark, on the waterfront near Jack London Square. The problem with the site is that — like Dodger Stadium — it’s across the freeway and more than a mile away from the nearest BART station in Downtown Oakland. A BART or streetcar extension is too costly, so the team is also examining the gondola option.

A gondola can be a fun way to get around, and the prospect of an elevated ride over the freeways with nice views of the surrounding California hills and neighborhoods could entice a lot of fans. But gondolas can’t carry a lot of people. For example, the Dodgers gondola would only move 5,000 people an hour, while the A’s one has been estimated at 8,000 an hour at the most. That’s pretty puny for games that could routinely attract 30,000 or more fans. The lines and backup would be massive.

But at the same time, if 5,000 Dodgers fans came by gondola, that’s almost 10 percent of a sellout crowd. That 10 percent reduction in traffic and parking volumes could be significant for the team and fans who drive.

The A’s gondola plan would have the additional benefit of providing year-round service to the shops, bars, and homes at Jack London Square. Chavez Ravine, by contrast, is a parking lot wasteland when there aren’t events going on. So that should be a mark in favor of the A’s plan, as the gondola there might be more likely to have sufficient ridership year-round to justify the costs.

Either way, both of these proposals appear to have private backing, which means taxpayers wouldn’t necessarily be on the hook. If the gondola option can work logistically and financially, it could be an interesting transit option for baseball fans — and potentially be a transit boon for the surrounding neighborhoods, too.

With the baseball postseason here, it seems fitting to think about how climate change will affect the national pastime. The early research reveals some interesting results, per the Atlantic, centered mostly on bigger hits in hotter weather:

With the baseball postseason here, it seems fitting to think about how climate change will affect the national pastime. The early research reveals some interesting results, per the Atlantic, centered mostly on bigger hits in hotter weather:

“If we change the density of the atmosphere near the surface of the earth, that will influence the behavior of objects that are thrown or hit through the atmosphere,” he writes. “That of course includes baseballs. Lower density means less air resistance, which would mean balls would get hit farther.”

In other words, all conditions being equal, a long fly ball that reaches the warning track in April might be a home run on a scorching day in July.

With the heat though will come more exhausted players, which could lead to more injuries and possibly worse defense and fewer stolen base attempts (I’m guessing). Or maybe more limber players from the heat will avoid injury?

But another impact could be related to the emotional side of the game:

Hot weather’s ability to stir up aggressive behavior has been well documented. According to a 2013 study published in the journal Science, “climate’s influence on modern conflict is both substantial and highly statistically significant.” Baseball, it seems, is no exception. As Larrick points out, “When we’re in an agitated state, we’re more ready to see hostility and want to retaliate.”

Basically, we may get more hit batters and fights on the field.

But the article fails to mention possibly the biggest impact: with rising sea levels, coastal cities like Miami may be completely underwater by the end of the century, while ballparks on the water like AT&T Park in San Francisco may be either abandoned or surrounded by sea walls. So a Marlins vs. Giants playoff game may one day be an impossibility, regardless of how the teams play.

More immediately, Major League Baseball may soon face a shortage of ash baseball bats, due to an insect infestation killing off the trees, which could be caused in part by a changing climate.

All in all, some interesting changes to contemplate for baseball fans. Take me out to the ballgame — while you still can.

Now that Major League Baseball’s American League plays the National League during the regular season and not just during the World Series, we have some interesting nicknames for series within or near metropolitan areas.

In honor of Opening Day today, it’s worth reviewing these nicknames to give us insight into the urban character of the cities, and in particular the way people are physically connected within or between them:

- Oakland Athletics vs. San Francisco Giants: the “Bay Bridge Series” — It’s all about the waterway bisecting this metropolitan region.

- New York Yankees vs. New York Mets: the “Subway Series” — Travel in New York is all about the subway.

- Chicago White Sox vs. Chicago Cubs: the “Crosstown Series” — Supposedly this one is also nicknamed the “Red Line Series” after the connecting train line. But you get a sense of the intimacy of Chicago from this nickname.

- Baltimore Orioles vs. Washington Nationals: the “Beltway Series” — Despite being an East Coast city, Washington DC is pretty auto dependent and has bad traffic on the beltway. Of course the heart of Washington DC is very transit-oriented.

- Tampa Bay Rays v. Miami Marlins: the “Citrus Series” — I’ll give it to the series’ boosters for not going with a highway name on this one and trying to reinforce the agriculture angle (for a state that will be mostly underwater due to sea level rise in the coming century).

- Kansas City Royals v. St. Louis Cardinals: the “I-70 Series” — These cities are far apart, so I give them a pass on the nickname. But they should use the Amtrack line name between these cities: the Missouri River Runner. A “River Runner Series” would be cool.

- Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim vs. Los Angeles Dodgers: the “Freeway Series” — Not much to add here. If Dodger Stadium moved downtown, it could be the “Metrolink Series.” Maybe it should be called that anyway, just to give a struggling rail line a marketing boost.

But enough about cities and transportation. Play ball!

Some local officials in Los Angeles may be sad that developer AEG is abandoning its dream of a downtown football field. The future Farmers Field was supposed to solidify the emergence of downtown Los Angeles as a destination and boost ridership on game days from the adjacent rail lines.

Public officials were very supportive. State lawmakers gave AEG a pass on environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act (technically AEG received an accelerated judicial process with agreed-upon, stringent mitigation measures).

From a transit perspective, the news isn’t great. The two other football stadium options in Los Angeles are fairly far out there, with one in Carson and another in Inglewood. These locations are not nearly as centrally located as Farmers Field would have been in terms of rail service and walkability.

But ultimately this may be a bullet dodged for Los Angeles. Football fields are generally a waste of valuable downtown real estate. There are only eight home games a year in the National Football League, and maybe two pre-season games. 10 games out of 365 days? That’s a waste of space for the vast majority of the year.

Sure, the venue can also host soccer games, concerts and maybe some giant outdoor conventions, like if the Pope ever visits. But most of the time it would be idle.

If you’re going to build a sports stadium downtown, it really should be for baseball. You get 81 home games a year with baseball, which means a lot of days and nights with thousands of pedestrians streaming in and out of local shops. Baseball also attracts a more mellow crowd than football, in my experience, so you don’t have the same “drunken brawl” factor (notwithstanding some recent high-profile incidents of baseball fan rage).

Hopefully AEG will find a much better use for that huge parcel downtown. Studies seem to support the idea that more housing, office and retail gives you a better bang for your buck, in terms of economic development and ridership.

In the end, downtown LA will probably come out farther ahead without Farmers Field.