California’s Central Valley is the state’s defining geographical feature. It’s the country’s breadbasket, with over 400 commodity crops, including all the almonds grown in the country. At the same time, it’s poverty-stricken, with Fresno the second poorest city in the U.S., and yet oil rich down by the deeply Republican Bakersfield.

California’s Central Valley is the state’s defining geographical feature. It’s the country’s breadbasket, with over 400 commodity crops, including all the almonds grown in the country. At the same time, it’s poverty-stricken, with Fresno the second poorest city in the U.S., and yet oil rich down by the deeply Republican Bakersfield.

It’s also one of the most environmentally vulnerable region in the state, with one of the most polluted air basins in the country. And as the Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay Area regions say no to new housing, sprawl is spreading into the Valley from these areas, as workers choose cheap housing and super commutes. Sprawl is also the norm around the Valley’s large cities along Route 99 on the eastern side. Like Los Angeles before it, the flat terrain means the region has no real geographical impediments to sprawl.

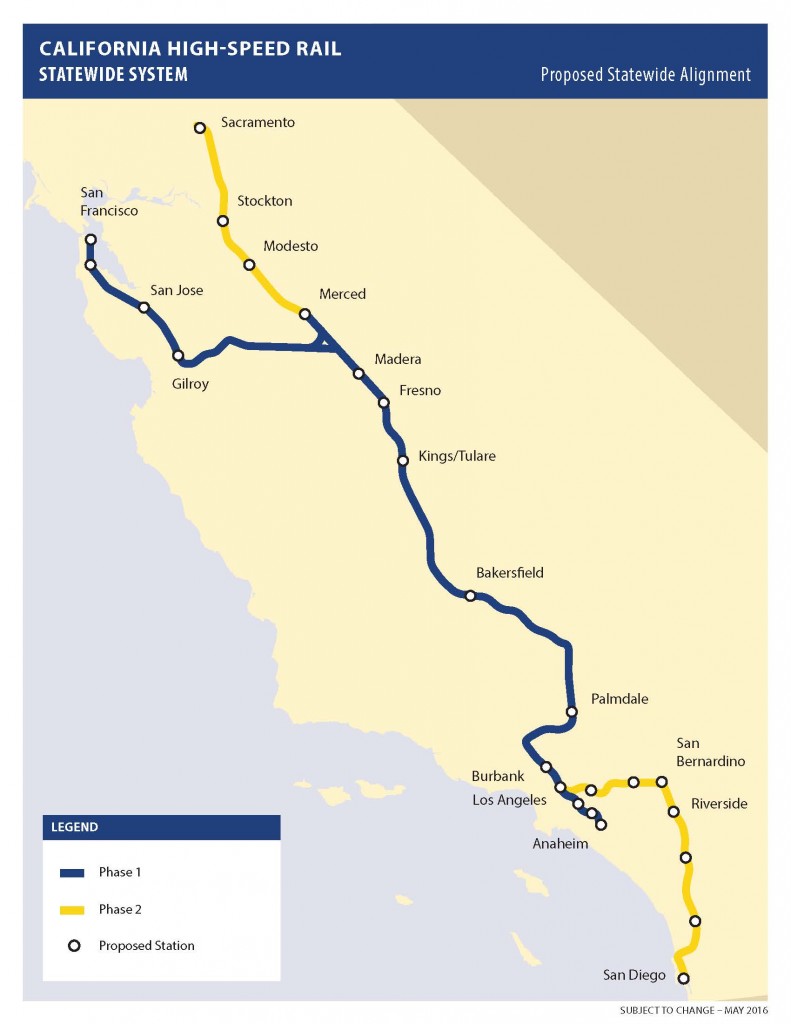

High speed rail could make the sprawl even worse, as the train will spur growth in places like Fresno, which will be just an hour or so from the booming coastal job centers (Berkeley and UCLA Law released a report on the subject in 2013, along with recommendations to combat the problem).

High speed rail could make the sprawl even worse, as the train will spur growth in places like Fresno, which will be just an hour or so from the booming coastal job centers (Berkeley and UCLA Law released a report on the subject in 2013, along with recommendations to combat the problem).

People in the Valley are well aware of the risk. Former Fresno mayor Ashley Swearengin, a rare Republican high speed rail supporter, tried to do the right thing to encourage more downtown-focused growth in Fresno and not allow the urban core to get hollowed out by competition from nearby cheap sprawl.

But Mayor Swearengin and other downtown booster’s efforts are threatened by Fresno’s neighbor Madera County next door, whose leaders prefer the model of continued sprawl over productive farmland and open space. The result will be the usual negatives we see elsewhere in the state: more traffic, worse air quality, and lost natural resources.

Marc Benjamin and BoNhia Lee detailed the new sprawl projects in the Fresno Bee last year:

Madera County is on the verge of a building boom that creates the potential for a Clovis-sized city north and west of the San Joaquin River, with construction starting this spring.

Riverstone is the largest of the approved subdivisions in the Rio Mesa Area Plan. It’s underway on 2,100 acres previously owned by Castle & Cooke on the west side of Highway 41 and north and south of Avenue 12. Castle & Cooke had plans to build there for about 25 years.

It’s the first of several subdivisions in the county’s area plan to be built. Over the past 20 years, Riverstone and other projects were targeted in lawsuits, many of which have been settled, but some still linger. But some critics contend that the new developments will worsen the region’s urban sprawl.

Principal owner Tim Jones’ vision for his nearly 6,600-home development a few miles north of Woodward Park is a subdivision with six separate themed districts. Riverstone will compete for home buyers with southeast Fresno, northwest Fresno, southeast Clovis and a new community planned south and east of Clovis North High School.

The Rio Mesa Area Plan will result in more than 30,000 homes when built out over 30 years. About 18,000 homes have county approval. The contiguous communities could incorporate to create a new Madera County city that could dwarf the city of Madera and have a population greater than Madera County’s current population of 150,000.

In the coming years, an additional 16,000 homes are proposed in Madera County. On the east side of the San Joaquin River, in Fresno County, about 6,800 homes are approved in the area around Friant and Millerton Lake.

Defenders of these sprawl projects claim that some are mixed-use developments located close to distributed job centers, minimizing the chances that they will become merely bedroom communities of Fresno. But as the development continues outward, it undercuts the market for infill housing, leading to a vicious downward spiral that we saw hit downtowns throughout the country in the middle of last century.

The best way to solve these growth issues is better regional cooperation, particularly around some type of urban growth boundaries. The growth boundaries can be de facto through mandatory farmbelts, rings of solar facilities, and possibly better pricing on sprawl projects to account for their externalities. Or they can be actual limits on growth and urban expansion outside of already-built areas.

Without concerted action, and with the high speed rail coming from Fresno to San Francisco soon, we may soon find that it’s too late to undo the damage in the Central Valley.