This question vexes so many transit advocates, when we look at the relatively high costs to build fixed transit in the U.S. (and other English-speaking countries) compared to other advanced economies around the world. It’s a subject I tackled indirectly in my book Railtown on the history of the Los Angeles Metro Rail system and directly in the 2022 Berkeley Law report Getting Back on Track.

Now Los Angeles documentary film producer and editor Nick Andert is tackling the question in an engaging, informative and in-depth piece he posted on YouTube, featuring an interview with yours truly and Alon Levy of NYU.

For transit nerds and those who care about improving mobility in American cities, I highly recommend it:

Californians would greatly benefit from fast, electrified high speed rail. But the system currently under construction is badly behind schedule and lacks funding to finish. It’s a warning to the rest of the country about our ability to build big, climate-friendly infrastructure.

Vox.com produced a video describing the challenges, featuring some words from yours truly:

I’m pleased to co-author a new study released today by the Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) at UC Berkeley Law that identifies the primary factors underlying cost and schedule overruns for rail transit construction and presents policy recommendations to overcome key barriers.

Improving rail transit delivery is critical for meeting climate and equity goals, given that the transportation sector contributes the majority of the state’s total greenhouse gas emissions. Since the bulk of these emissions come from private automobile travel, rail transit—from heavy-rail subways to overhead-powered trolleys—offers low-emission and low-cost commuting and travel options across income levels.

However, in California and throughout the United States, rail transit infrastructure projects have long suffered from cost overruns and deployment delays that reduce the value of investment and erode public trust. These state and nation-wide projects lag international peers.

For example, completed U.S. heavy rail projects (with trains powered from below via an electric “third rail”) cost more than twice as much on average than their European, Canadian, and Australian counterparts, while U.S. light rail projects (powered by overhead electric lines) cost around 15 percent more than similar projects in Europe, Canada, and Australia. In the United States, different governance authorities hold veto power over multiple decision points, and lack of alignment between these authorities can derail regionally-crucial projects.

Some of the largest and highest-profile California projects, such as the second phase of the Silicon Valley Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) extension into San José, are particularly slow and expensive. How can California deliver high-quality rail transit projects while keeping on budget and on schedule? Although transit ridership has fallen during the COVID-19 pandemic, ridership is beginning to rebound and transit agencies are committing billions to new infrastructure.

With funding from California SB 1 research dollars through the UC Berkeley Institute of Transportation Studies, CLEE analyzed national and international construction trends and assessed five California rail case studies that offer examples of delivery issues and methods to address them. Common challenges included lack of megaproject management capacity and expertise; project design and scope creep; lack of agency coordination; inefficient procurement and contracting methods; and need for excessive stakeholder outreach.

The five case studies included rail transit projects in Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, and San José, as well as California’s statewide high-speed rail project (which is not a traditional intracity rail line but will be vital to state efforts to reduce vehicle travel). Drawing on the lessons learned from these five cases, CLEE recommends state, regional and local transit leaders consider:

- Forming regional collaboratives to house permanent expertise not tied to any individual local project, with staff available to consult with or contract out to projects when needed. Such a collaborative could benefit projects like the Bay Area Rapid Transit Berryessa Extension, where multi-agency oversight of different project elements required dedicated coordination and communication.

- Creating a statewide office to provide dedicated staff support/ technical assistance to facilitate coordination among local and regional agencies or offer additional funding to agencies that provide detailed plans for addressing any in-house staffing needs, as applicable. For example, the San Francisco Central Subway involved complex construction in a high-density residential and commercial district with significant overruns and delays, in part because agency staff had less megaproject experience than contractor teams. California High-Speed Rail similarly struggled with sufficient in-house capacity, particularly during its early stages.

- Using project procurement and delivery methods that includes early contractor involvement to ensure the total cost of building expensive projects in dense, complex areas is identified before construction begins. For example, the San Diego Mid-Coast Corridor Trolley successfully utilized the construction manager/general contractor or construction manager-at-risk contracting method (CMGC/CMAR), in which the project owner engages a designer and a construction manager separately during the design phase, and the owner and construction manager negotiate a guaranteed maximum price for construction prior to design completion before starting the build phase. This method helped ensure that this relatively pricey project stayed on budget.

- Legislatively granting master permitting authority to transit agencies with priority rail transit projects (including engineering, street closure, and similar project completion-critical permits) to reduce delays and costs imposed by local governments or large or powerful stakeholders along the route. For example, Los Angeles Purple Line Section 1 leaders coordinated with local governments to align expectations about restricted construction times and locations, as local governments held permitting authority over the transit agency.

- Avoiding the addition of significant, non-essential betterments and limiting bespoke design for extraneous station elements (e.g., complex facades), particularly after the design stage. Multiple case study projects suffered from expensive, over-designed project elements to appease stakeholders along the route with effective veto power and other leverage. Determining who will pay for these modifications is a crucial decision point that can push a transit project over budget and behind schedule, if not appropriately managed. State and federal leaders could condition funding on avoiding outcomes that delay a project or place unreasonable cost expectations on the agency and its contractors.

You can read the full report as well as a short policy brief.

Register for a free webinar on Thursday, January 27 at 10:00am Pacific time to learn about the report’s top findings with an expert panel including:

- Hasan Ikhrata, Executive Director of the San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG)

- Brian Kelly, CEO of the California High-Speed Rail Authority

- Therese McMillan, Executive Director of the Metropolitan Transportation Commission

Thanks to my report co-authors Katie Segal, Ted Lamm and Michael Maroulis.

President Biden is nearing a potentially significant bipartisan win on federal infrastructure spending, as a $550 billion package nears approval in the United States Senate. But the United States has a poor track record of spending this kind of money wisely, particularly on rail transit.

As the Eno Center has documented, U.S. taxpayers pay a premium of nearly 50 percent on a per-mile basis to build rail transit compared to our global peers. Tunneled projects furthermore take nearly a year and a half longer to build than abroad

In a piece I just published for Smerconish.com, I lay out key requirements that federal leaders should consider including as conditions on these “Biden bucks” to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past. To summarize the piece, federal transit dollars should:

- Include measures that prevent local transit agencies from “over-designing” projects to appease narrow interests with counter-productive and costly concessions;

- Ensure local leaders choose optimal rail transit routes to boost ridership and overall utility and cost-effectiveness;

- Streamline federal permitting, including via multi-agency coordination and expedited environmental reviews, with exemptions from analysis on impacts not all that relevant to environmentally beneficial rail – like traffic, air quality, and noise;

- Incentivize smart procurement of contractors, including a maximum on contract size to break up the work on large projects among smaller and more competitive firms;

- Give transit agency staff more flexibility on construction oversight, including ability to make basic decisions on project implementation to speed construction; and

- Require 24/7 construction to shave potentially years off construction timelines.

With a challenge this complex, no single solution will cure the United States of its poor track record on rail transit project delivery. But the infrastructure bill now gives Congress and the Biden Administration an opportunity to start fixing the problem — delivering climate-friendly infrastructure quickly and effectively to more people.

Dr. Martin Wachs, who passed away Sunday evening, was California’s preeminent transportation scholar. He knew both Northern and Southern California well, having joined UCLA’s urban planning department in 1971 and founded its Institute of Transportation Studies, while also spending a decade at UC Berkeley in the interim, where he chaired that’s schools transportation studies program. Much of our knowledge about the history of the state’s transportation system and our ability to evaluate its efficacy comes from his prolific scholarship and role as a public commenter on major transportation decisions.

But more than that, he was a humble and generous person with boundless curiosity and intellect. I first met him when I was researching the history of the Los Angeles Metro Rail system, back in 2007. His influence on Los Angeles transit debates was all over the archival and media documents I found from the 1970s and 1980s, from his scholarship to his op-eds to his conference appearances. Los Angeles elected leaders took his research seriously, even if they didn’t like his skepticism about rail transit in a city as spread out as Los Angeles.

I had originally approached the book as a rail enthusiast, and when I met him in his then-RAND office a few blocks from my Santa Monica apartment, he seemed aghast that I would set out to write a book that would promote rail. But he nonetheless provided me with contact information for a former student who had researched Metro Rail history, along with a few large binders of research for my files. I thanked him profusely and relied on his research for much of the discussion in the book on L.A.’s rail history. In fact, much of what we know about the demise of the Pacific Electric streetcar system in Southern California and its myth-busting conclusion that it was not a car company conspiracy is due to his groundbreaking research.

When my book Railtown was finally published seven years later in 2014, Marty was invited to co-present with me on its findings at an event at UC Berkeley. Top faculty at the school lined up to greet him, like fans seeking autographs at a celebrity book signing. It was an impressive indication of his impact and role as a longtime mentor and generous colleague to so many of them. He was like a returning rock star in his field.

While I was a bit worried how he would react to the book, his comments that evening were thoughtful and ultimately complimentary. I chronicled them at the time on this blog. They are worth reading for anyone interested in his take on rail. What stood out to me was his comment that the book showed him how little politicians actually heeded the advice of transportation scholars, as they forged a path for rail investments despite the caution of experts. And as a recent member of the high speed rail peer advisory group, he was finding a similar dynamic at play, with politicians making short-sighted decisions on this crucial California infrastructure project that have come back to haunt and potentially torpedo its progress.

After that evening in 2014, we kept in touch, even co-authoring an article series on the pros and cons of rail transit investments. If I ever had any questions or needed advice or resources, Marty would jump at the chance, providing thoughtful responses, lists of resources to review, and people to contact. Hundreds of others could say the same thing — his legions of former students now working on urban planning issues, his colleagues, and countless leaders and readers who have benefited from his scholarship and thinking on these complicated issues. You can read some of their tributes (and find out how to honor his memory) on this UCLA website.

Just a few months ago I contacted him about a new rail transit study we’re conducting at UC Berkeley Law. Typical Marty, he immediately offered to schedule a Zoom with our team, providing invaluable advice. But what I remember now is his initial email back to me, where he reflected on his life during the pandemic times. Like most of us, he was home-bound, and he missed his children and grandkids. But he was enjoying his work (including a manuscript in progress that I hope will be finished somehow) and took solace in his garden.

I pictured him in the warm Southern California sun tending to his plants and wonder now who will care for them with his absence? It’s just a small example of the giant hole his death leaves in our world. But Marty’s amazing legacy — beyond the scholarship and influence on public debates — includes his many former students, colleagues, and friends. He trained and supported so many well, who can do their best now to carry on the work he advanced, on issues that affect so many people’s daily lives.

Rest in peace, Marty, and thank you.

If you’re interested in the past, present and future of rail transit in Los Angeles, check out the video above from my talk this week with Streets For All. My moderated comments begin about 20 minutes in. We covered everything from the dismantling of the Los Angeles streetcar network to delays building current rail lines to whether anyone alive today will ever get to ride high speed rail.

And if you don’t know Streets For All, they’re a volunteer-based organization advocating for equitable redesign of streets and the transportation network to favor transit, walking and biking, as a climate change and quality-of-life necessity in Los Angeles.

Consider becoming a member if you’re interested in these issues. I thank them for hosting me for this talk!

With the presidential election over, Joe Biden faces a U.S. Senate that still hangs in the balance. But even with a Democratic runoff sweep in Georgia next month, it will be very divided. So what will be possible for a President Biden and his administration to achieve on climate change?

Agency action, foreign policy changes, and spending can all make a difference on emissions, with any COVID stimulus and budget deals with Congress, if feasible, providing potential avenues for further climate action. Here are some ideas along those lines, broken out by key sectors of the economy.

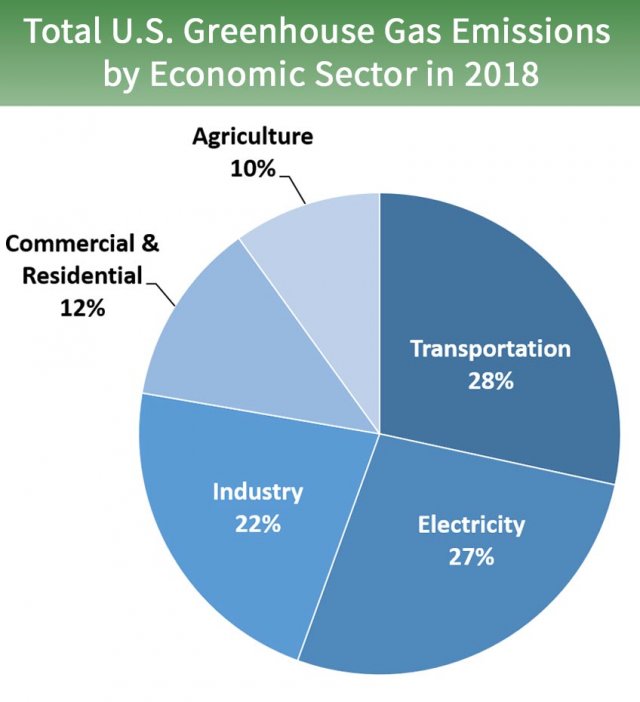

Action on Transportation

As the EPA chart above of 2018 emissions shows, transportation contributes the largest share of nationwide greenhouse gas emissions at 28%. The best way to reduce those emissions is to decrease per capita driving miles through boosting transit and the construction of housing near it, as well as switch to zero-emission vehicles, primarily battery electrics.

Transit-oriented housing is largely governed by local governments, who generally resist construction. Absent state intervention or federal legislation from a divided Congress, the Biden administration will have to make surgical regulatory changes directing more grant funds to infill housing and potentially use litigation and other enforcement tools to prevent and compensate for racially discriminatory home lending and racially exclusive local zoning and permitting practices.

On transit, a Biden administration would be very pro-rail, especially given the President-elect’s daily commuting on Amtrak in his Senate days. If the Senate flips to the Democrats, high speed rail could be a big part of any bipartisan COVID stimulus package, if it happens, which would be a lifeline to the California project that is otherwise running out of money. Other urban rail transit systems could benefit as well, and the U.S. Department of Transportation could favor and streamline grants for transit over automobile infrastructure. Notably, LA Metro CEO Phil Washington, responsible for implementing the nation’s most ambitious rail transit investment program in Los Angeles County, is chairing Biden’s transition team on transportation.

On zero-emission vehicles, Biden may have relatively strong tools to improve deployment of this critical clean technology. First, perhaps through a budget agreement with Congress, he could reinstate and extend tax credits for zero-emission vehicle purchases, which have expired for major American automakers like General Motors and Tesla. Second, he could use the enormous purchasing power of the federal government to buy zero-emission vehicle fleets. And perhaps most importantly to California, his EPA can rescind its ill-conceived attempt at a fuel economy rollback for passenger vehicles and then grant the state a waiver under the Clean Air Act to institute even more stringent state-based standards, toward Governor Newsom’s new goal of phasing out sales of new internal combustion engines by 2035.

Reducing Electricity Emissions

The electricity sectors comes in a close second place, with 27% of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions. The move toward renewable energy, particularly solar PV and wind turbines, is so strong that even Trump had difficulty slowing it down during his single term in office, in order to favor his fossil fuel supporters. But nonetheless, the Trump administration created some strong headwinds which can now be reversed.

First and foremost, President-elect Biden can drop the tariffs on foreign solar manufacturers, which drove up prices for installation here in the United States. Second, as with the zero-emission vehicle tax credits, a budget deal with Congress could bolster the federal investment tax credit for solar, which steps down from the initial 30% toward an eventual phaseout for residential properties and 10% for commercial properties. The credit could also be extended to standalone energy storage technologies, like batteries and flywheels, if Biden budget negotiators play their hands well (easy for me to say). A Biden administration could also improve energy efficiency by dropping weak regulations on light bulbs and appliances like dishwashers at the U.S. Department of Energy and introducing more stringent ones instead.

Legislatively, any COVID stimulus deal (again, if it happens) could potentially contain money for a big renewable energy buildout, including for new transmission lines, grid upgrades, and technology deployment. In terms of regulations, if Biden is able to get any appointments through the Senate to agencies like the Federal Regulatory Energy Commission (FERC), that agency could make climate progress by simply letting states deploy more renewables and clean tech, including demand response, as well as potentially supporting state-based carbon prices (a move supported by Trump’s FERC appointee Neil Chatterjee, which promptly resulted in his demotion last week).

Slowing Fossil Fuel Production

The two big moves for the Biden administration will be to stop new leases for oil and gas production on public lands (including immediately restoring the Bear’s Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments) and bringing back the methane regulations on oil and gas producers that the Trump administration rolled back. As a bonus, his Interior Department could engage in smart planning to deploy more renewable energy on public lands, where appropriate, including offshore wind.

Other Climate Action

The list goes on for how the Biden administration can embed smart climate policy into all agencies and facets of government, with or without Congress. Of particular note, his appointees at financial agencies like the Federal Reserve and U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission could bolster and require climate risk disclosures for institutional and private investors. The U.S. Office of Management and Budget could ramp back up, based on the best science and economics, the social cost of carbon, which represents the cost in today’s dollars of the harm of emitting a ton of carbon dioxide equivalent gas into the atmosphere. This measure provides much of the economic justification for the federal government’s climate regulations. And of course, President-elect Biden can have the U.S. rejoin the 2015 Paris climate agreement immediately upon being sworn in (though the country will need to set a new national target).

Overall, Biden’s win means the U.S. will regain some climate leadership at the highest levels, with much that can be done through congressional negotiations, agency action, and spending. However, the stalemate in the US Senate likely means that any hopes for big new climate legislation will be dashed. As a result, continued aggressive action at the state and local level, as well as among the business community, will be critical to continue to help push the technologies and practices needed into widespread, cost-effective deployment to bring down the country’s greenhouse gas footprint.

One election certainly won’t solve climate change, and the costs continue to rise to address the impacts we’re already seeing from extreme weather. But given the current political climate, the actions described above could allow the U.S. to still make meaningful progress to reduce emissions over the next four years and beyond, even in an era of divided government.

On January 27, 2017, just one week after Trump’s inauguration, UC Berkeley Law’s Henderson Center for Social Justice held a daylong “Counter Inauguration,” featuring various panels in reaction to Trump’s victory. I spoke on an afternoon panel that day entitled “Monitoring the Environmental, Social and Governance Impacts of Business in the Trump Era” and offered my predictions on what the Trump years would bring for environmental law and policy.

I recently reviewed these predictions, three months out from the upcoming November election, to see how they measured up against the reality of Trump’s near-complete term in office. Bottom line: these predictions mostly tracked with what happened with Trump and his administration’s leaders, albeit with some steps I missed, some that never came to pass, and some positive outcomes for environmental protection.

First, I predicted the Trump Administration would follow through on the campaign pledges to boost fossil fuels in the following ways:

- Opening up public lands for more oil and gas extraction

- Slashing regulations that limit extraction and related pollution, such as the Clean Power Plan and methane rules

- Weakening fuel economy rules for passenger vehicles

- Financing more infrastructure that could boost automobile reliance (i.e. more highways and less transit)

These were all relatively predictable actions, and they all pretty much happened as predicted. On public lands and fossil fuels, Trump rolled back National Monument protection at Utah’s Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante, as well as streamlined permitting for oil and gas projects on public lands. On environmental rules in general, here is a list of 100 environmental regulations that the administration has tried to reverse. On vehicle fuel economy standards, here’s my article on EPA’s proposed rollback. And transit funding went from 70 percent of transportation grants under Obama to 30 percent under Trump, with the rest funding highways.

Second, I predicted that his administration would try to undermine clean technologies by:

- Weakening tax credits for renewables and electric vehicles

- Undoing federal renewable fuels program

- Revoking California’s ability to regulate tailpipe emissions

- Attempting to undermine California’s sovereignty to regulate greenhouse gases through legislation

- Cutting funding for high speed rail and urban transit

- Withdrawing from Paris agreement

On these predictions, I was correct on most accounts. The administration did weaken tax credits for renewables (both by not extending them or preventing them from decreasing over time, save for a recent one-year extension on wind energy as a budget compromise) and electric vehicles (by letting them expire and threatening to veto Democratic legislation that would have extended them in a recent budget bill). His EPA did revoke California’s waiver to issue tailpipe emission standards. And he famously withdrew from the Paris agreement (to take actual effect later this year) and has tried to cancel almost $1 billion in high speed rail funding in California.

But I was incorrect that the administration would pursue legislation to preempt California’s (and other states’) sovereignty to set their own climate change targets. There was little appetite in Congress to do so, though Trump’s Justice Department did seek unsuccessfully to declare California’s cap-and-trade deal with Quebec to be unconstitutional. And his record on renewable fuels is more mixed but did deliver some gains to corn-based ethanol producers, though the environmental benefits are suspect with this type of biofuel. I also failed to predict the administration’s efforts to impose tariffs on foreign solar PV panels and wind turbines, which slowed those industries somewhat.

Finally, I predicted some possible bright spots for the environment in the Trump years, much of which did occur:

- Clean tech generally has bipartisan support in congress

- Infrastructure spending in general could be negotiated to benefit non-automobile investments

- Lawyers can stop or delay a lot of administrative action on regulations

- A shift will happen now to state and subnational action on climate, which probably needed to happen anyway

Sure enough, clean technology, particularly solar PV, wind and batteries, has continued to increase in the Trump years, though not at the same pace as under Obama due to the policy headwinds. But infrastructure spending has definitely favored automobile interests, as noted above.

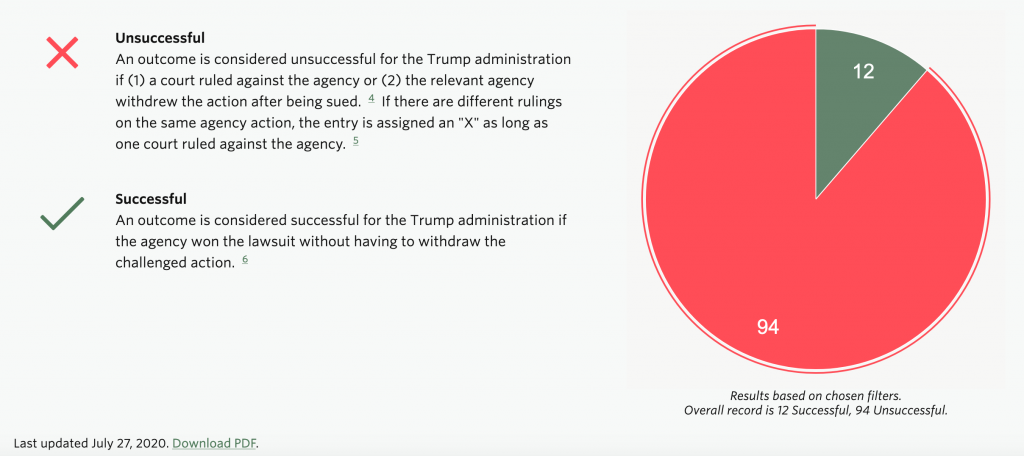

But more importantly, two critical predictions did come to pass. First, attorneys have successfully stopped most administrative rollbacks. In fact, the administration has an abysmal record defending its regulatory actions in court. As NYU Law’s Institute of Policy Integrity has documented, the administration has lost 94 cases in court and won only 12 to date, as tracked in this chart:

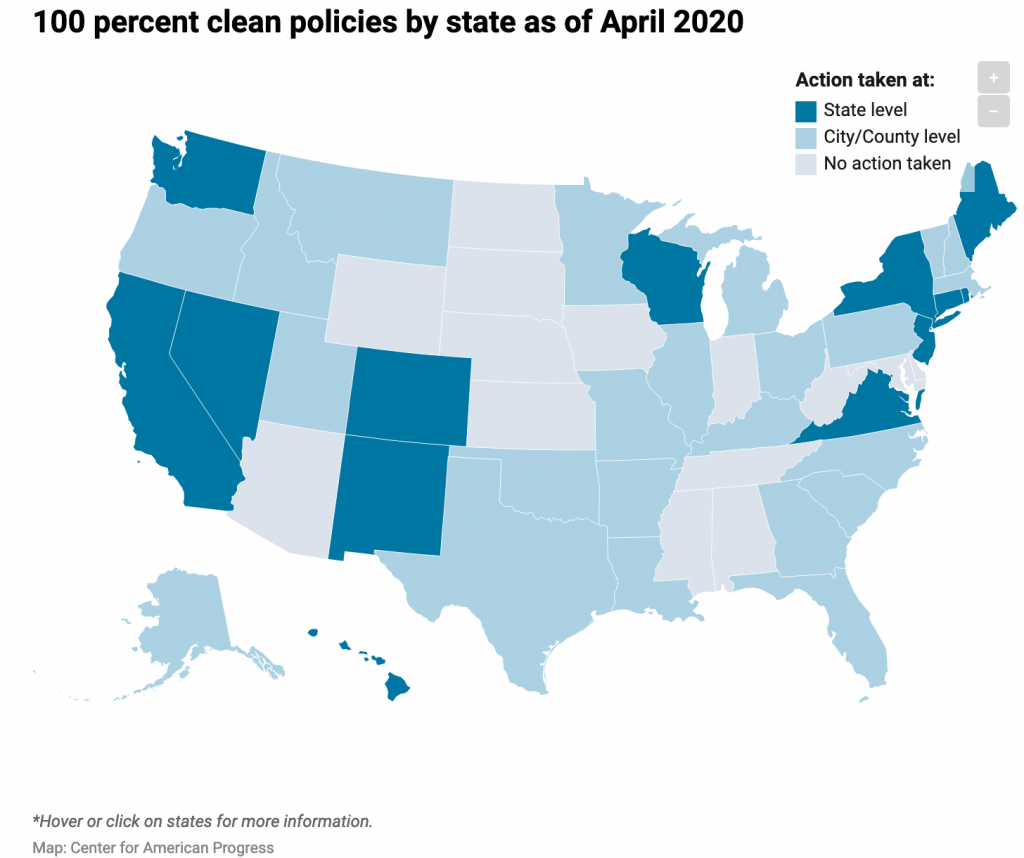

And perhaps more importantly, the lack of federal climate action has moved the spotlight to state and local governments, which often have significant sovereignty to enact aggressive policies that add up to serious national climate action. Take renewable energy, for example, per the Center for American Progress, with this map of states and municipal governments that have enacted 100% clean electricity standards:

And on clean vehicle standards, 13 states plus the District of Columbia now follow California’s aggressive zero-emission vehicle standards, representing about 30 percent of the nation’s auto market.

As a result, in many ways, environmental law and climate action appears to have survived the Trump term in office mostly intact, despite losing progress and facing some setbacks on key issues. Most of the regulatory actions can be reversed by a new administration, while Congressional action during the Trump years was relatively minimal in scope. Meanwhile, the counter-reaction to Trump spurred some significant policy wins at the state and local level.

But while one term is perhaps survivable for environmental law and climate progress, a second one could paint a completely different picture. So the stakes certainly remain high this November.

Aaron Gordon at Vice News tackles one of the most pressing subjects on transportation & climate policy: why does the U.S. absolutely suck at building public transit? Whether it’s a bus-rapid transit lane or high-speed rail, the U.S. cannot build these projects anywhere near on time or at a reasonable cost, compared to other advanced economies.

Some examples:

New York City is responsible for the most expensive mile of subway track on Earth, at $3.5 billion per mile, the first segment of the Second Avenue Subway. The second phase is projected to crush that record.

And these statistics:

“Nearly all American urban rail projects cost much more than their European counterparts do,” [transportation scholar Alon] Levy wrote in Citylab. “The cheaper ones cost twice as much, and the more expensive ones about seven times as much.” This includes both heavy rail (subways) and light rail. “Only a handful of American [light rail] lines come in cheaper than $100 million per mile, the upper limit for French light rail.”

So how does Gordon explain the ineptitude? He cites multiple factors, but the big ones seem to be the following:

- Political compromises on routes and station locations, which drive up costs and turn transit projects into “political consensus” projects — a phenomenon I observed quite clearly and documented in my 2014 book Railtown on planning and building Los Angeles Metro Rail.

- Over-reliance on expensive consultants rather than cheaper in-house expertise. This dynamic is a function of the piecemeal, start-and-stop federal and state funding for transit, which means local agencies can’t build up the expertise they need. It’s also a function (in my view) of corruption, as special interests like contractors and labor unions cut deals for big contracts with minimal oversight.

- Overlapping and poor governance in a system of hyper-local control, in which multiple agencies have jurisdiction over projects, resulting in long permitting times and costly compromises.

Gordon is short on solutions in his piece but promises more to come. Meanwhile, other scholars such as Alon Levy and researchers at the Eno Center are also working on this issue. Hopefully we can see some promising reforms get traction soon, because the present situation in the United States is unsustainable and wasteful, in multiple ways.

The San Francisco Bay Area’s population and job centers are famously divided by the bay itself, with jobs and housing on the San Francisco side accessed by commuters to the east via the Bay Bridge or the transbay BART tube. The dream for unlocking access via more transit — and possibly high speed rail — depends on building a second tube

ABC 7 News covered the most recent plans for a potential project, featuring a short clip of me:

This is a subject we covered on my very first City Visions show as a host back in 2016. Regardless of what shape it takes, one thing we know for sure is a second transbay tube will take longer and probably cost more to build than the current plans will estimate. But such a project will be critical for long-term sustainable mobility in the region.