On January 27, 2017, just one week after Trump’s inauguration, UC Berkeley Law’s Henderson Center for Social Justice held a daylong “Counter Inauguration,” featuring various panels in reaction to Trump’s victory. I spoke on an afternoon panel that day entitled “Monitoring the Environmental, Social and Governance Impacts of Business in the Trump Era” and offered my predictions on what the Trump years would bring for environmental law and policy.

I recently reviewed these predictions, three months out from the upcoming November election, to see how they measured up against the reality of Trump’s near-complete term in office. Bottom line: these predictions mostly tracked with what happened with Trump and his administration’s leaders, albeit with some steps I missed, some that never came to pass, and some positive outcomes for environmental protection.

First, I predicted the Trump Administration would follow through on the campaign pledges to boost fossil fuels in the following ways:

- Opening up public lands for more oil and gas extraction

- Slashing regulations that limit extraction and related pollution, such as the Clean Power Plan and methane rules

- Weakening fuel economy rules for passenger vehicles

- Financing more infrastructure that could boost automobile reliance (i.e. more highways and less transit)

These were all relatively predictable actions, and they all pretty much happened as predicted. On public lands and fossil fuels, Trump rolled back National Monument protection at Utah’s Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante, as well as streamlined permitting for oil and gas projects on public lands. On environmental rules in general, here is a list of 100 environmental regulations that the administration has tried to reverse. On vehicle fuel economy standards, here’s my article on EPA’s proposed rollback. And transit funding went from 70 percent of transportation grants under Obama to 30 percent under Trump, with the rest funding highways.

Second, I predicted that his administration would try to undermine clean technologies by:

- Weakening tax credits for renewables and electric vehicles

- Undoing federal renewable fuels program

- Revoking California’s ability to regulate tailpipe emissions

- Attempting to undermine California’s sovereignty to regulate greenhouse gases through legislation

- Cutting funding for high speed rail and urban transit

- Withdrawing from Paris agreement

On these predictions, I was correct on most accounts. The administration did weaken tax credits for renewables (both by not extending them or preventing them from decreasing over time, save for a recent one-year extension on wind energy as a budget compromise) and electric vehicles (by letting them expire and threatening to veto Democratic legislation that would have extended them in a recent budget bill). His EPA did revoke California’s waiver to issue tailpipe emission standards. And he famously withdrew from the Paris agreement (to take actual effect later this year) and has tried to cancel almost $1 billion in high speed rail funding in California.

But I was incorrect that the administration would pursue legislation to preempt California’s (and other states’) sovereignty to set their own climate change targets. There was little appetite in Congress to do so, though Trump’s Justice Department did seek unsuccessfully to declare California’s cap-and-trade deal with Quebec to be unconstitutional. And his record on renewable fuels is more mixed but did deliver some gains to corn-based ethanol producers, though the environmental benefits are suspect with this type of biofuel. I also failed to predict the administration’s efforts to impose tariffs on foreign solar PV panels and wind turbines, which slowed those industries somewhat.

Finally, I predicted some possible bright spots for the environment in the Trump years, much of which did occur:

- Clean tech generally has bipartisan support in congress

- Infrastructure spending in general could be negotiated to benefit non-automobile investments

- Lawyers can stop or delay a lot of administrative action on regulations

- A shift will happen now to state and subnational action on climate, which probably needed to happen anyway

Sure enough, clean technology, particularly solar PV, wind and batteries, has continued to increase in the Trump years, though not at the same pace as under Obama due to the policy headwinds. But infrastructure spending has definitely favored automobile interests, as noted above.

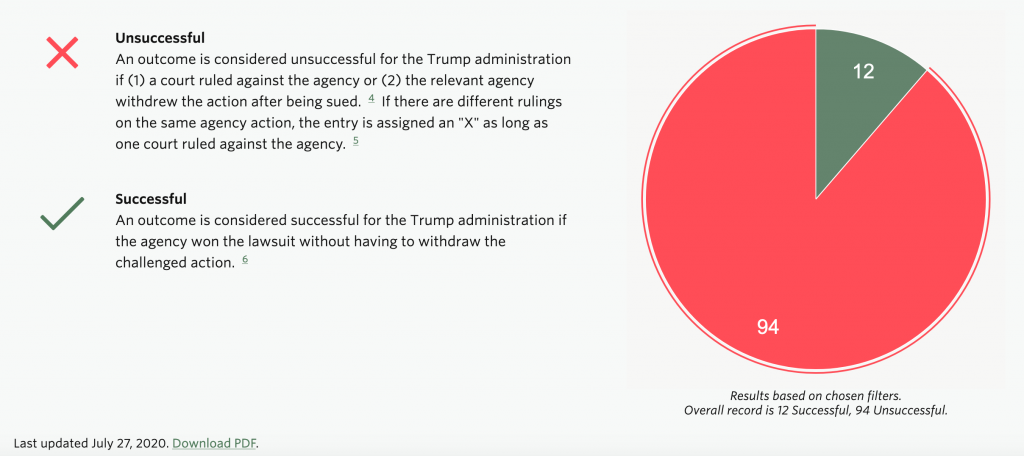

But more importantly, two critical predictions did come to pass. First, attorneys have successfully stopped most administrative rollbacks. In fact, the administration has an abysmal record defending its regulatory actions in court. As NYU Law’s Institute of Policy Integrity has documented, the administration has lost 94 cases in court and won only 12 to date, as tracked in this chart:

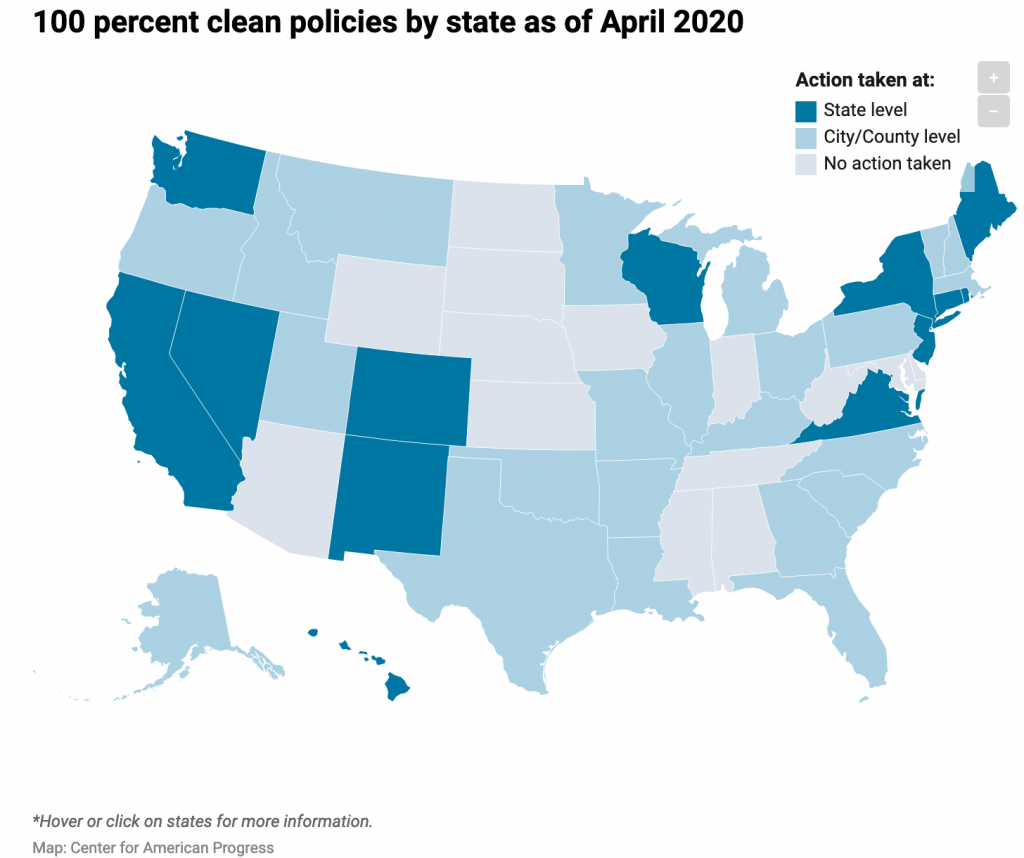

And perhaps more importantly, the lack of federal climate action has moved the spotlight to state and local governments, which often have significant sovereignty to enact aggressive policies that add up to serious national climate action. Take renewable energy, for example, per the Center for American Progress, with this map of states and municipal governments that have enacted 100% clean electricity standards:

And on clean vehicle standards, 13 states plus the District of Columbia now follow California’s aggressive zero-emission vehicle standards, representing about 30 percent of the nation’s auto market.

As a result, in many ways, environmental law and climate action appears to have survived the Trump term in office mostly intact, despite losing progress and facing some setbacks on key issues. Most of the regulatory actions can be reversed by a new administration, while Congressional action during the Trump years was relatively minimal in scope. Meanwhile, the counter-reaction to Trump spurred some significant policy wins at the state and local level.

But while one term is perhaps survivable for environmental law and climate progress, a second one could paint a completely different picture. So the stakes certainly remain high this November.