As the United States grapples with racism and police brutality in the wake of the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers, environmentalists need not be bystanders in the debate over solutions. Environmentalism has multiple opportunities to help address institutional racism, and few issues cross cut racism and environmentalism more than housing policy.

Environmentally, housing policy that encourages urban development is crucial to reducing emissions from automobiles through decreased commute times and car dependency, as well as limiting development pressure on open space and agricultural land. And from a racial and economic justice perspective, more inclusive housing policy is vital to undoing pervasive residential segregation in America today.

While the Civil Rights movement and the resulting laws helped make explicit racism illegal in housing, predominantly white local governments and their allies can still legally practice housing racism through restrictive local zoning and permitting processes. As Michael C. Lens and Paavo Monkkonen from UCLA’s Luskin School of Public Affairs documented in a recent study, local restrictions on housing density and complex housing approval processes are highly correlated with wealthy residents walling themselves off from those with diverse incomes and of different races. And the more hands-off a state government is on housing policy in favor of “local control,” the more segregated the state will be.

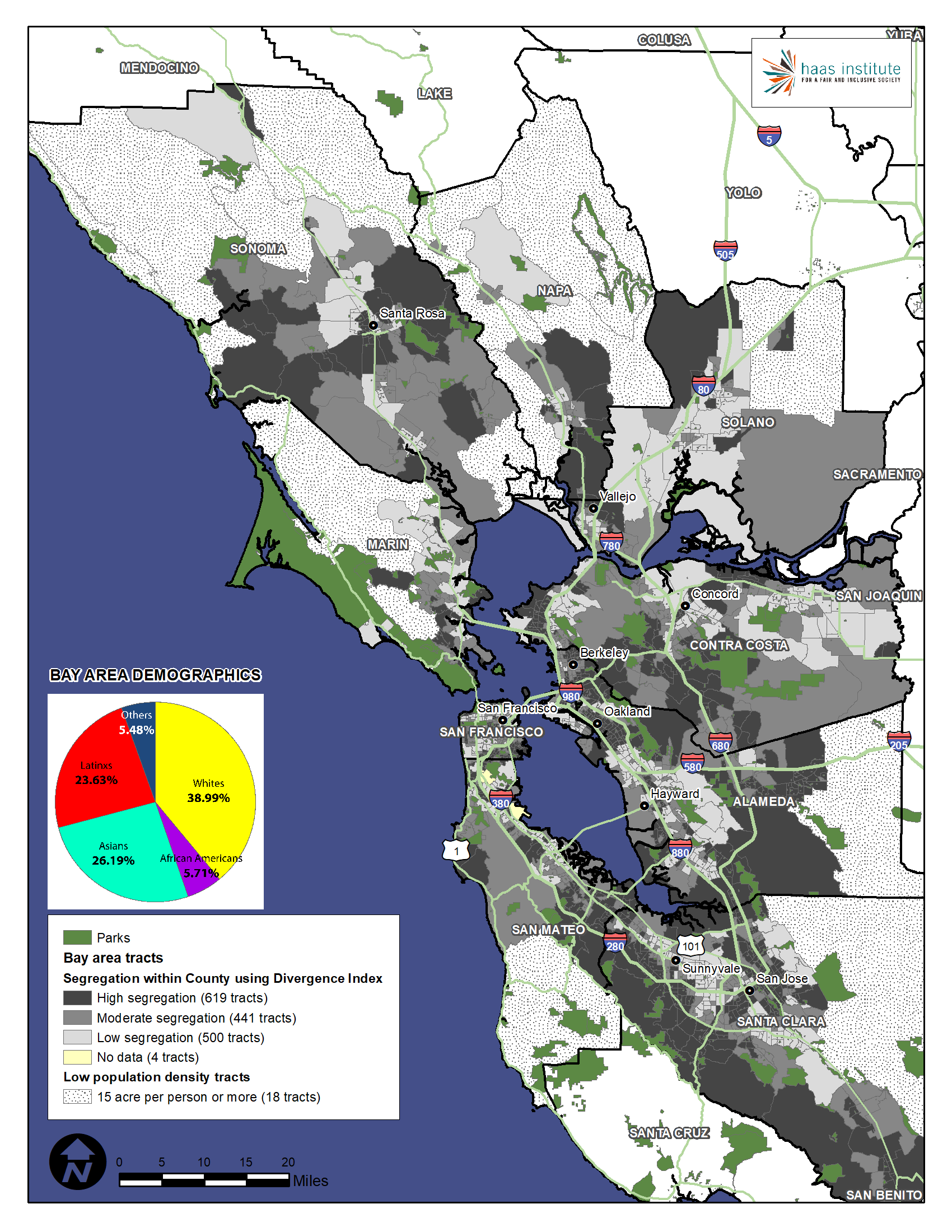

You can see this dynamic in stark terms in the San Francisco Bay Area. UC Berkeley researchers Stephen Menendian and Samir Gambhir comprehensively mapped racial demographics throughout the region, and found that whites are the most segregated racial group in the region. Although whites are just under 40 percent of the Bay Area’s population, 184 of 1582 census tracts are more than 75 percent white, with 359 tracts more than 66 percent white and 663 tracts more than 50 percent white (see map below). Contra Costa County alone in the East Bay features some of the most racially segregated white neighborhoods in the entire Bay Area: Walnut Creek (63 percent white) and Martinez (69 percent white), with Lafayette at 77 percent white (a city that was a recent New York Times poster child for exclusionary local land use policies).

The Los Angeles metro area fared no better, as the 10th most segregated metropolitan area in the country, according to one index.

So what can be done to address this fundamental form of racial segregation? Simply put, the state and federal government need to intervene to ensure that local governments cannot practice racially and economically exclusionary local zoning. By limiting the number of apartment buildings and affordable homes that are built in their communities, high-income whites are limiting racial diversity in their communities, while sending a message to people of color with incomes to afford to live in these areas that they are not welcome.

Earlier this year, the California State Senate debated a bill (SB 50 by Sen. Wiener) that would have accomplished just that: making it illegal for high-income areas to prevent apartment buildings and affordable homes near major transit. Yet a majority of state senators — many from these segregated, high-income areas, including Contra Costa, Malibu, West LA, and Silicon Valley — voted against it.

If Black Lives Matter, then surely black neighbors should too. California, like many other states around this nation, needs to address this root cause of segregation — to achieve outcomes of both environmental sustainability and racial justice.

The California State Senate this morning (for a second time after an initial vote last night) narrowly and finally killed SB 50, a major climate-land use bill that would have allowed apartment buildings near major transit stops and job centers. Despite high-profile opposition from some low-income tenants groups, the senators voting against the bill largely represent affluent suburbs.

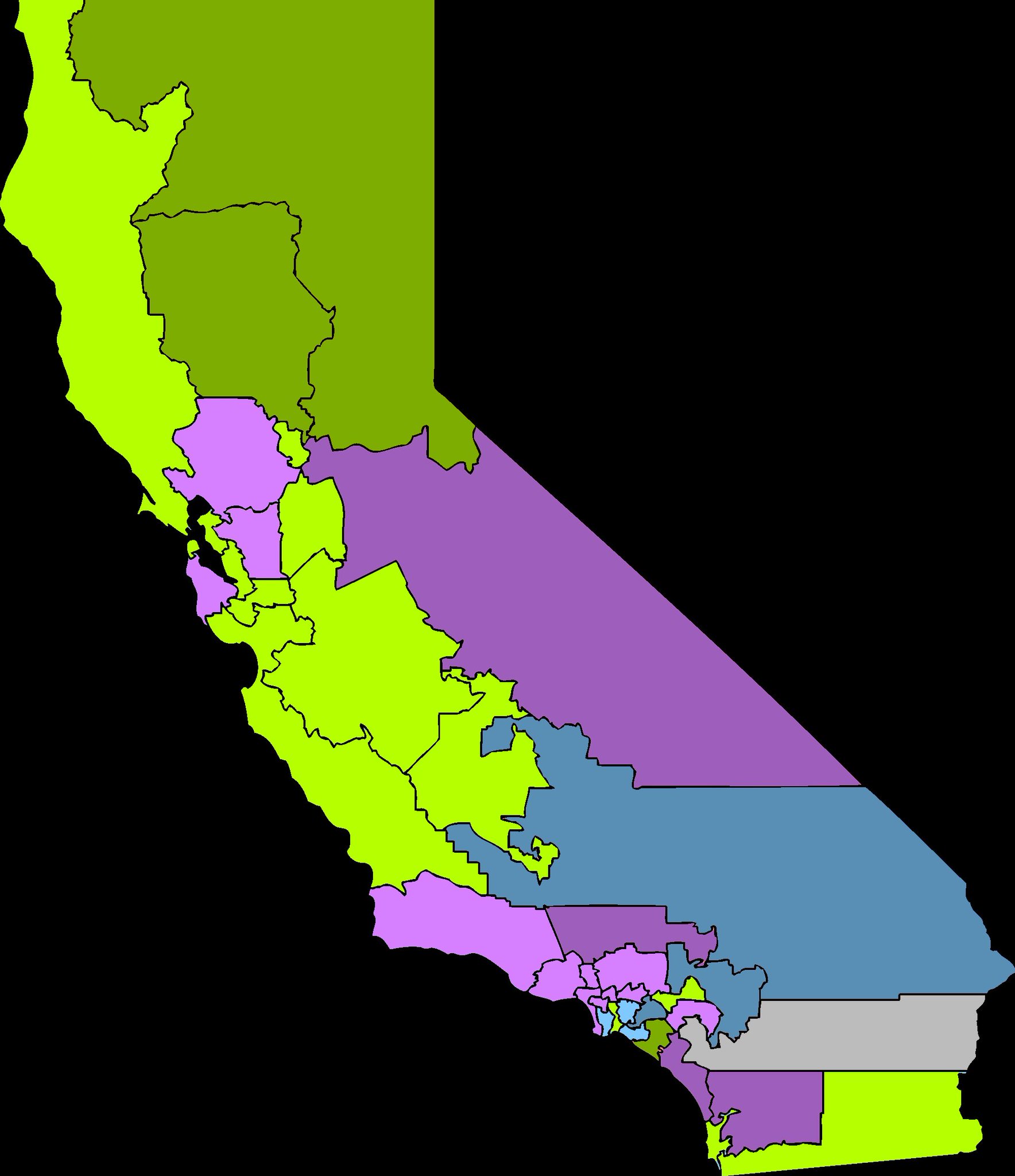

To illustrate the geographical divide, a Twitter user put together this map of the senate districts and votes, with purple opposed, green in support (light for Democrat and dark for Republican), and blue abstaining:

As you can see, the “opposed” senators largely cluster along on the affluent coastal and suburban areas. This dynamic is particularly apparent in the San Francisco Bay Area, where representatives of the urban core supported the bill (including bill author Sen. Scott Wiener and Sen. Nancy Skinner). But the senators representing the suburban, high-income Silicon Valley communities (Sen. Jerry Hill), affluent East Bay suburbs (Sen. Steve Glazer), and the Napa area (Sen. Bill Dodd) were all opposed.

Meanwhile, Southern California Democrats representing high-income coastal suburbs were almost uniformly opposed:

- Sen. Hannah-Beth Jackson, representing Santa Barbara communities;

- Sen. Henry Stern, representing Malibu and suburbs north of urban Los Angeles;

- Sen. Ben Allen, representing the Westside of Los Angeles, including Manhattan Beach and Beverly Hills;

- Sen. Anthony Portantino, representing La Cañada Flintridge and who had unilaterally shelved the bill last year in his committee; and

- Sen. Bob Hertzberg, representing the San Fernando Valley.

Notably, there were some standout “profiles in courage” votes in favor of the bill, including:

- Sen. Lena Gonzalez from Long Beach, despite opposition from city leaders in her district;

- Sen. Brian Dahle from the conservative, northern inland part of the state, who recognized the damage sprawl does to farmland;

- Sen. Bill Monning of Carmel who spoke passionately about the inequality and devastating commutes wrought by exclusive local land use policies; and

- Sen. John Moorlach of coastal Orange County, a Republican (and bill co-author) who appreciated the legislation giving more property rights to landowners.

What were the argument of opponents? They largely involved these issues:

“The bill will not produce enough affordable housing.” The bill in fact contained minimum requirements that projects receiving benefits under the bill include affordable units. As a result, SB 50-type reform would result in the biggest boost to subsidized affordable units in the state’s history, at possibly a seven-fold increase.

“SB 50 takes away local control.” To the contrary, the bill would give low-income communities five years to develop local plans for infill housing and two years for other communities to plan to meet these standards. Locals would be free to set more aggressive standards on affordability and relax restrictions even more if they wanted to do so. SB 50 also did not alter local permit approval processes. Furthermore, for senators who profess to care about the housing shortage, local control is the single biggest cause of the shortage, particularly through restrictive zoning.

“The bill will lead to gentrification and displacement.” This is a real, yet overstated, concern that the bill addressed with numerous provisions to protect against new developments displacing low-income tenants (a massive, ongoing problem that predates SB 50 and is made worse by the exclusionary housing policies SB 50 was designed to prevent). Furthermore, local governments were free to go beyond those protections. Second, as UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation documented, any projects under the bill only “pencil” in high-income areas where developers get higher returns. Finally, as the Urban Displacement Project at UC Berkeley (in collaboration with researchers at UCLA and Portland State) found, new market-rate and affordable housing at a regional scale reduces gentrification and displacement overall.

Finally, Sen. Henry Stern uniquely argued against the bill for encouraging development in high-fire zones. It was an odd argument, considering that the SB 50 zones around transit are in some of the only non-fire, urban zones in the state, while the bill contained explicit language preventing application in high-severity zones. Furthermore, encouraging growth in infill areas reduces pressure to sprawl into the same wildlands Sen. Stern is worried about. Yet Sen. Stern was convinced that the protections weren’t strong enough and conceivably was worried that the provision in the bill allowing conversion of single-family homes into fourplexes would put more people into harms way. Given this logic, will Sen. Stern now support a bill banning new construction in high-fire zones? Or would he have supported the bill with an amendment banning such construction? He did not respond to these questions on his Facebook page.

So what’s next? The bill or some form of it could be brought back this legislative session as a “gut-and-amend” of an existing bill. Indeed, Senate pro tem Toni Atkins vowed shortly after the vote to bring a housing production bill back before the legislature this session. Supporters could also try a more limited approach, such as exempting controversial parts of the state from the bill.

Otherwise, given the long-term problem and entrenched opposition to change, the fact that such a landmark bill only fell three votes short is quite an accomplishment. Since the problem will only get worse, the political pressure to act will increase. That means that something like SB 50 will ultimately pass in California. It will be too late for those priced out in the near term, and possibly too late to address our 2030 climate goals, which will require reduced driving miles from housing closer to jobs and transit absent major technological innovation. But it will happen, because reforming our land use governance is the only way to solve this problem.

As the debate over SB 50 and other state legislative efforts to boost California’s housing supply heats up, it’s worth reviewing some of the data about how dire the housing situation is in the state. Here are some tidbits:

High Home Prices and Rents:

- According to the California Legislature’s Legislative Analysts Office, the average California home costs about two-and-a-half times the average national home price, at $440,000 (and much higher in major metro areas). This price divergence began in the 1970s, when California home prices went from 30 percent above U.S. levels in 1970 to more than 80 percent higher by 1980.

- Per the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD), the majority of California renters (more than 3 million households) pay more than 30 percent of their income toward rent, while nearly one-third (more than 1.5 million households) pay more than 50 percent of their income toward rent.

- Per a Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice study, 19% of community college students in California are homeless, while 60% are considered “housing insecure.”

- Almost one-quarter of all homeless people in the country live in California, according to federal data.

Extreme Housing Shortage Relative to Demand:

- California ranks 49th among all U.S. states in housing units per resident, behind only Utah, where residents tend to have large families in single homes, per a 2016 McKinsey study. The McKinsey analysis showed that California has 358 homes per 1,000 people, whiles comparable states like New York and New Jersey have more than 400 homes per 1,000 residents.

- HCD calculated that the state needs to build 180,000 additional homes annually, but over the last ten years housing production has averaged fewer than 80,000 new homes each year (and is currently declining).

Local Zoning is a Key Barrier:

- While the 2016 McKinsey study presented a goal of 3.5 million units needed to address the shortage and stabilize prices, UCLA’s Lewis Center found that California cities and counties currently only zone for a combined 2.8 million new housing units. And many of these zoned parcels are located in rural areas far from jobs, which is not where housing is needed.

- The New York Times recently mapped the local zoning in some major cities and found that 75 percent of Los Angeles and 94 percent of San Jose is zoned exclusively for single-family homes.

- UC Berkeley’s Terner Center documented via a statewide survey of local governments that in two-thirds of California’s cities and counties, multifamily housing (i.e. apartments) is allowed only on less than 25 percent of the available land.

- The Terner Center similarly showed that fully one-half to two-thirds of all land in California is reserved exclusively for single family homes.

- In 1933, according to University of Texas’s Andrew Whittemore, less than 5 percent of Los Angeles’ zoned land was restricted exclusively restricted for single-family homes. By 1970 though, half of the land in Los Angeles was zoned only for single family residences, per UCLA’s Greg Morrow.

- Morrow noted that zoning in Los Angeles went from allowing up to 10 million residents in 1960 to 3.9 million residents by 1990.

Local Permitting Processes Remain a Major Barrier:

- The Terner Center estimated that local permit and impact fees on new units average $150,000 per unit.

- Environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), triggered when local governments make permitting decisions discretionary as opposed to ministerial, ranked as the ninth biggest barrier to housing overall, according to the Terner Center survey of planners.

- The Rose Foundation found that CEQA litigation affects fewer than 1 out of 100 projects not already exempt from the law, while litigation has been steady at about 195 lawsuits per year on average since 2002.

These numbers on California’s housing crisis show not only the human cost of the shortage, but the need for a strong policy response to fix the governance system that exacerbates the problem. We’ll see if this legislative session brings any change.

California Governor Gavin Newsom campaigned on solving the state’s infamous housing affordability woes. In 2017, he promised 3.5 million housing units by 2025, or 500,000 per year. This boost in supply would serve to stabilize prices and relieve the crushing burden that housing costs create for working and low-income residents.

But with the legislative tabling last week of SB 50, the only bill in the legislature to upzone neighborhoods near transit and jobs, that goal now appears to be infeasible. Gov. Newsom’s signature issue is already looking to be a failure.

Why? California is currently zoned for 2.8 million units, as UCLA Luskin comprehensively documented. And many of those planned units are in areas not in need of new housing, such as in rural, fire-prone parts of the state with low demand. Furthermore, as the study authors point out, the planned units may face other obstacles to getting built, such as permitting challenges. In short, massive upzoning is required to meet the Governor’s goals.

Sure, it’s only a few months into Gov. Newsom’s term, so couldn’t solutions emerge later? Here’s the problem: by tabling this effort into an election year (2020), legislative appetite to address the fundamental cause of the problem (resistance from affluent, predominantly white suburbs) will wane further. And even if the legislature acts in future years, it will still take years for the changes on the ground to take hold, as communities likely resist these zoning changes by enacting more permitting obstacles. At that point, the 2025 goal will be out of reach. The state needs to start the solutions now.

Interim steps certainly exist, such as strengthening the affordable housing allocations the state gives to local governments. But with at least a 700,000 zoning shortfall statewide to get to 3.5 million units, those steps will hardly make a dent.

So far, the Governor has not wanted to take an aggressive stance to save upzoning measures like SB 50. As Liam Dillon of the Los Angeles Times reported on the shelving of SB 50, Newsom stated the following yesterday:

“To the extent that we can find a pathway to take core components of SB 50 and getting it over the finish line, I’m committed to helping support that effort,” Newsom said.

But Gov. Newsom apparently did not step in to shepherd SB 50 in the state senate, as Gov. Brown did in 2017 to extend the cap-and-trade program in the face of legislative resistance.

There is still time, and credit is certainly due to Newsom for championing this issue (Gov. Brown, by contrast, viewed the politics as too intractable to try very hard). But the crisis is real, and words are not enough. Action, leadership, and courage are required, and the window of opportunity for real solutions may soon be closing.

California faces a dual crisis: a massive housing shortage leading to displacement and spiraling economic inequality; and an increase in driving miles and related greenhouse gas emissions which threaten to undermine the state’s progress achieving its climate goals. Both of these crises were solidly addressed in Sen. Scott Wiener’s SB 50, which seeks to ease local restrictions on housing development near transit and jobs, in part so more residents can access transit and shorter commutes.

The bill sailed through its first two policy committees, with bipartisan support and only one vote against it in each. Labor unions, business groups, and key environmental groups like NRDC supported it. Yet as my Legal Planet colleague Jonathan Zasloff posted yesterday, Sen. Anthony Portantino, chair of the appropriations committee, unilaterally suspended the bill until January next year.

Sen. Portantino’s political career started out in the affluent Los Angeles suburb of La Cañada Flintridge, a community of mostly upper income homeowners. Residents’ general state of housing security contrasts sharply with the rest of the region, with the city’s average household income in 2015 at $214,496, compared to a median income in Los Angeles County that year of $54,510. The city was also ranked the 71st wealthiest city in the U.S. by Bloomberg. In short, it is a community with residents who aren’t likely to feel the brunt of the housing affordability crisis and in fact are likely benefiting from it through increased property values.

Sen. Portantino’s arguments against the bill cited some familiar objections, such as the bill would increase gentrification (false: new construction under the bill would almost exclusively occur in high-income areas), it’s one-size-fits-all (false: it is tailored to counties by population and areas by transit frequency, with the exception of a statewide provision permitting fourplex renovations), and that it will discourage transit expansion if a new rail line would come with strings attached on land use (to which the obvious response is: why would we want to spend taxpayer dollars on expensive transit lines to low-density communities?).

He also argued that incentives would work better to convince local governments to allow more housing. Yet what incentives does Sen. Portantino and others who espouse this view believe will work to induce city councils in upscale communities like Palo Alto, Beverly Hills and La Cañada Flintridge to allow multifamily housing, particularly for a variety for income levels? These are wealthy communities that will not be moved by the prospect of more state dollars. Indeed, in recent years, some of them (like Corte Madera in Marin County) even tried to secede from regional transportation agencies to avoid having to comply with state mandates to build low-income housing — that’s right, they’d rather sacrifice state transportation dollars than live next to low-income people.

Sen. Portantino’s unilateral action to hold the bill until next year now places the burden on Senate president Toni Atkins to override this decision and allow SB 50 a vote by the full senate. It also places a burden on Governor Newsom, who has pledged to build 3.5 million housing units in the state and expressed tentative support for the concept of SB 50. Yet as UCLA’s Luskin Center documented, the state’s current zoning only allows for 2.8 million units, and most of those units are likely in places where we wouldn’t want to see new growth, such as in far-flung, fire-prone regions. In short, the Governor cannot achieve his signature campaign goal without significant statewide upzoning, as SB 50 would produce.

Will state leaders step up to resuscitate to the bill? Is it too late at this point? Or will those currently suffering from housing insecurity and lack of affordable places to live have to wait until next year for a solution, when an upcoming election may darken its prospects for passage? Certainly other bills in Sacramento seek to address aspects of the housing shortage, but only SB 50 presented a comprehensive, meaningful solution to a crisis that is well past time to solve in this state.

I’ll be discussing SB 50 (Wiener) on KQED Radio’s Forum this morning from 9am. The bill heads to its final committee hearing this Thursday before a full vote in the California State Senate.

As I’ve written before, SB 50 is the state’s first and only major attempt at comprehensive “upzoning” (relaxing local restrictions on housing) near transit and jobs. It also recently added a provision to legalize the conversion of single-family homes into duplexes, triplexes or fourplexes anywhere in the state.

Tune in at 88.5 FM in the San Francisco Bay Area and weigh in with your questions. Even if you don’t live in the Bay Area, you can stream it live and call in or email with questions.

Yesterday was a big day for SB 50 (Wiener), the bill to upzone residential areas near transit and jobs. The bill faced a potentially hostile Senate Governance and Finance Committee, chaired by State Senator Mike McGuire from Sonoma County and author of the rival Senate Bill 4. Despite the treacherous path, the outcome was a decisive win with only one vote against (Sen. Hertzberg of Los Angeles), albeit with significant amendments to the bill.

The new bill language has not been released, but based on the committee discussion and follow-up statements from Sen. Wiener and his office, the amendments essentially appear to do two big things (among other changes):

- Exempt SB 50 from counties with populations less than 600,000, except for cities within those counties with populations over 50,000 that have rail or ferry stops (see the green/purple parts of the flow chart below)

- Legalize “by right” permitting of single-family homes into duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes across the state, albeit with only minimal demolition of existing structures allowed.

The amendments now make the overall bill relatively complex, but Berkeley-based artist Alfred Twu drew up this handy flow chart to explain how the bill will now work:

For a graphic on the counties now affected, here is a map from Barak Gila with the counties over 600,000 population (in which SB 50 applies) in yellow:

So did Marin County get a carve out, in a deal to merge the bill with county representative McGuire’s SB 4? Notable cities now apparently exempted from SB 50 include the SMART train and ferry stop in Larkspur and the ferry-stop towns of Sausalito and Tiburon. Yet San Rafael and Novato (two SMART train stops) are still covered by SB 50.

What about Sonoma County? Cities with SMART trains that no longer would be under SB 50 jurisdiction include Cotati, Rohnert Park, Cloverdale, Healdsburg, and Windsor. Still included are Petaluma and Santa Rosa.

In Southern California, Santa Barbara County’s Goleta and Carpinteria Amtrak stations also would not be covered by SB 50, while the City of Santa Barbara would still be affected.

Meanwhile, notable other cities with rail or ferry stops within those non-yellow counties, to which SB 50 will still apply, include Vallejo, Fairfield, Vacaville, Roseville, Rocklin, Madera, Modesto, Merced, Davis, Chico, Redding, and Salinas. And of course the remaining yellow counties represent major population and employment centers that could greatly increase housing production with SB 50 upzoning.

On balance, this new population criteria is not a bad compromise, as it means most of the core areas of California that prevent new housing are still affected. But the SMART train line is pretty well decimated by this compromise, as is the Santa Barbara Amtrak line. It’s a relatively small but painful price to pay, given the potential benefits statewide with the remaining areas.

Meanwhile, the fourplex by-right provision could potentially open up significant densification in California everywhere, a la the recent Minneapolis plan to end single-family zoning and allow triplexes city-wide. But could this new SB 50 provision encourage more high-density sprawl, with fourplexes in outlying areas that don’t have access to transit and therefore lead to more traffic and pollution? The original beauty of SB 50 (and its predecessor SB 827) was that it targeted transit neighborhoods to reduce overall driving miles. The fourplex provision could undermine those environmental benefits. Yet since the fourplexes (or other smaller divisions) can only involve minor demolition of existing structures (or building from the ground up on vacant parcels), the deployment may not be as sweeping as it might initially appear.

Overall, SB 50 cleared a major hurdle yesterday before its eventual advancement to the Senate floor, emerging relatively unscathed and with some potentially major new additions. If it passes that chamber, it will be on to the Assembly, with further carve-outs and compromises likely.

What’s the latest with California’s major proposed legislation to remove local restrictions on new housing near transit and jobs? I wrote back in December about Senate Bill 50 (Wiener), which would relax local requirements on density, parking, floor-area ratio and height (in some cases), for projects near transit and in high income “job-rich” communities that lack commensurate housing (read: Cupertino, home of Apple).

SB 50 also contains provisions to protect low-income renters from eviction from any new development under the bill and takes off the table (at least for the near future) large swaths of urban low-income areas deemed to be “sensitive communities.” For a visualization of what that means on the ground, see p. 11 (figure 5) of the CASA compact for a map of San Francisco Bay Area zones that would be exempted under this provision.

So how is the bill doing? Notably, SB 50 sailed through its first committee hearing last week with overwhelming approval. But it may face critical obstacles in its next hearing at the State Senate Governance and Finance Committee. That’s because that committee is chaired by State Senator Mike McGuire from Sonoma County, who authored a rival bill (Senate Bill 4) which would do much the same to relax local zoning near transit as SB 50, except with the big difference that it would exempt any “city with a population of 50,000 or greater that is located in a county with a population of less than 1,000,000” (which would exempt McGuire’s hometown of Healdsburg from the bill’s provision).

So the politics remain dicey going forward. The difference this year though is that Wiener has lined up powerful political support from organized labor, who like the job opportunities that would flow from more housing projects in urban areas. And by exempting in the near term “sensitive communities” with low-income tenants, Wiener has largely neutralized (for now) opposition from tenant groups who helped sink last year’s version, SB 827.

As a result, the opposition has so far been revealed as wealthy communities up and down California, who are resistant to allowing any new development or letting newcomers move in who can’t afford an expensive single-family home. They frequently use lines of attack like the bill is a “developer giveaway” or that proponents are “real estate shills.”

To counter these voices and win more support from advocates for low-income renters, Wiener has introduced amendments that tighten up the affordable housing requirements for any project that uses the bill’s provisions. Specifically, SB 50 now has ‘inclusionary zoning’ requirements in which developers with projects with between 20-200 units must make 15% of the units affordable to low-income residents (implemented on a sliding scale, with fewer units required if they’re available to extremely low-income residents), while 200-350-unit projects must provide 17% affordable units. Any project above 350 units must have 25% affordable units (also on a sliding scale depending on the income eligibility). Housing projects under 10 units are meanwhile exempt from providing any on-site affordable units, while projects of 10-20 units in size can pay in-lieu fees. With these provisions in place, the bill would likely lead to a significant deployment of subsidized affordable units to accompany new market-rate development.

But what practical effect will SB 50 likely have on the ground, assuming it can survive the messy politics and become law relatively intact? UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation and Urban Displacement Project conducted an interesting case study policy brief and found that any likely boost to new housing under SB 50 would mostly be small scale and in high-income communities, though that impact varies depending on whether other local restrictions are in place.

The UC Berkeley study involved a parcel and financial feasibility analysis on four representative neighborhoods in the state, with the following highlights:

- Developers will get a much higher return on SB 50 projects in upscale areas, even with the higher land costs, meaning that most projects will be built in these areas and not in low-income areas (as I argued back during the SB 827 debates last year).

- Most of the available parcels (at least in these four study areas) are too small to support big projects, meaning most development will likely be of the 12-unit or less variety; in addition, the bill’s restrictions on developing properties with tenants will likely take a significant number of parcels off the table (a good thing, from the point of view of protecting current tenants from eviction).

- High on-site affordable housing requirements (discussed above) will be financially feasible in upscale areas but could sink projects in lower-income neighborhoods that otherwise barely pencil, so Sen. Wiener may want to consider a less rigid approach to the affordable housing requirements and instead scale them based on the value of the project.

- Remaining local government restrictions, such as high setback requirements and bans on projects that cast too much shadow (which was a dealbreaker for an important housing project in San Francisco that the board of supervisors just killed because it would cast occasional shadows at an adjacent park), will still impede projects, even if SB 50 passes.

- Developers may choose to ignore the benefits of SB 50 if a local government has already made it easy to permit projects at the current, locally determined height and density limits, just to avoid a protracted permitting fight that would come with using new, state-allowed higher limits.

The findings from this study should be clarifying for the SB 50 debate going forward. First, they show the relatively limited impact that SB 50 might have on the ground, at least compared to some of the hyperbolic rhetoric and initial studies about the predecessor bill’s impact in specific areas.

Second, SB 50 will likely end up being a just step (albeit a big one) in the right direction on boosting housing supply to match demand. Further reforms (some under consideration in other bills being debated this session) will need to focus on streamlining the permitting process for projects consistent with this new zoning. Otherwise, local governments are likely to respond to SB 50’s passage by adding more steps to the permitting process in order to kill projects through delay and multiple veto points. State legislation may also need to address the other zoning restrictions on new development that SB 50 leaves untouched, such as the aforementioned setback and shadow limits.

California’s current housing shortage certainly didn’t happen by accident — it’s the result of a complicated web of politics that SB 50 and its backers are trying to undo, piece by piece. We’ll have to stay tuned as more studies assess the bill’s impact and Wiener entertains more political compromises to win over support.

Governor Newsom is making housing a top priority. His proposed budget devotes significant resources to housing production and homelessness, including:

Governor Newsom is making housing a top priority. His proposed budget devotes significant resources to housing production and homelessness, including:

- $500 million for local governments to address homelessness

- $500 million (from $80 million originally) for the state’s low-income housing tax credit

- $500 million for “moderate-income” housing production

- $25 million for homeless Californians to access federal disability programs

But public cash alone won’t solve the problem, given the scale of the need. Along these lines, Gov. Newsom correctly identified local restrictions on new housing as a key barrier. To address the intransigence, he proposed the revolutionary step of limiting local government access to gas tax funds if the jurisdiction is behind on its housing production.

But how do you define a local jurisdiction “not meeting” housing production? Right now, it’s a bureaucratic threshold, set by the state for each region, which then in turn sets housing targets for each city and county in the region. Historically though, these “regional housing needs allocations” have been weak and easily gamed (though this process will become more stringent going forward, based on recent legislation like AB 686 and AB 72).

So if Gov. Newsom relies on an opaque and uncertain state-derived metric, his policy may not be that effective in actually encouraging new housing production. And cities and counties are somewhat limited anyway in how much housing actually gets built in their jurisdictions, particularly if they’re in areas without much housing demand.

A better metric would involve assessing local zoning and permitting processes near major transit stops or in “low vehicle miles traveled” areas (if a local jurisdiction doesn’t have much transit). Cities and counties can certainly control those two aspects of land use. For example, cities that have upzoned and streamlined permitting near transit would maintain their gas tax funding. Cities and counties that restrict what can be built or require multiple layers of discretionary review would then lose access to dollars.

Sen. Scott Wiener’s proposed SB 50 would get the state far down that path already, but Gov. Newsom’s use of that kind of budget mechanism would add political heft to the approach.

And as an added bonus, it might actually work in encouraging responsible local land use policies to boost housing production in the right places.

The California housing debate took me to KQED-TV’s “Newsroom” program on Friday. You can watch my discussion with host Thuy Vu and State Sen. Scott Wiener, author of SB 50 to upzone areas near major transit, at the 18-minute mark: