Like the proverbial Betamax vs. VHS technology competition of the 1980s, EV fast charging has been caught up in a wasteful turf war involving three different formats, basically boiling down to Japan versus Europe/North America vs. Tesla. But now we suddenly have a winner, as first Ford and then General Motors and startup Rivian have all pledged in the past few weeks to adopt the Tesla charging standard in their vehicles starting next year, with adapters available for consumers this year.

It couldn’t happen soon enough. The differing charging formats means EV drivers are limited where they can get fast charging or have to carry adapters, while non-Tesla charging stations had to have multiple plugs available for different formats.

The other problem is that non-Tesla chargers are basically awful. They’re unreliable, clunky and often with low power. While legacy automakers dithered and refused to invest in a network of chargers, Tesla instead built a user-friendly, ubiquitous network. The company is now poised to reap the economic benefits, from its position as a dominant market leader in vehicle sales.

One of the big questions now is what happens to all the soon-to-be-obsolete chargers out there? Companies like EVgo and Electrify America have built thousands of fast-charger stations with formats that are now zombie technology. Worse, the public has invested significantly in these stations, with EVgo a creation of a $100 million legal settlement from the California energy crisis circa 2000, while Electrify America was funded with dollars from the Volkswagen “dieselgate” emissions cheating settlement, to the tune of almost $1 billion in California alone.

All will not be lost, as the stations can be retrofitted in some cases. The wiring is sometimes the hard part, so charger replacement by itself may not be too expensive. But in some cases, retrofits may be uneconomical. And ultimately, these companies are likely to go out of business, unless they can get access to Tesla’s intellectual property to build their own versions of a Tesla SuperCharger.

If not, Tesla will have a monopoly on charging stations, which will create its own long-term problems. But for now, the charging format wars have ended, in favor of a far superior product.

That’s something that both EV advocates and drivers can finally celebrate.

Tesla’s “Full Self-Driving” software was hit with a “recall” by U.S. safety regulators yesterday, due to concerns that the system malfunctions around intersections and does not consistently follow speed limits. I put “recall” in quotes because the company plans to send over-the-air software updates to the 363,000 affected vehicles, so no vehicle will be physically recalled to any service center.

I discussed the implications on KTVU News last night, along with the federal government’s default “hands off” approach when it comes to trusting automakers to follow safety requirements:

Car sales data from 2022 is now out, and the results are encouraging. According to the Wall Street Journal, automakers sold 807,180 fully electric vehicles in the U.S. last year, or 5.8% of all vehicles sold, up from 3.2% a year earlier. And as E&E News reported (paywalled) 19 percent of new car purchases in California were zero-emission vehicles. This is a big increase from the 12 percent in 2021, according to the same California Energy Commission data, and a positive trajectory to a state-mandated goal of 100% zero-emission vehicle sales by 2035.

But only one EV company dominates. Tesla Motors accounted for 65% of total EV sales last year, down from 72% in 2021, but with no real competition in sight. Ford Motor Co. is a distant number 2 in sales at just 7.6% of the U.S. market, with Hyundai and affiliate Kia combined at third with 7.1% market share. In California, the top vehicles sold overall by a large margin were the Tesla Model 3 followed by Model Y, with combined sales of more than half of all EVs sold in the state. What’s more, Tesla earns large profit margins per vehicle compared to other automakers.

Other legacy automakers appear to be asleep at the wheel (so to speak). They are instead largely committed to making money on gas guzzlers, despite press releases and limited EV releases to the contrary. General Motors, for example, is allocating only 10% of a new $860 billion investment into EV development, according to Eletrek.

But not everyone thinks Tesla’s lead will continue. As Paul Krugman wrote in December after a stock price drop:

[I]t’s hard to explain the huge valuation the market put on Tesla before the drop, or even its current value. After all, to be that valuable, Tesla would have to generate huge profits not just for a few years but in a way that could be expected to continue for many years to come.

He cited the lack of obvious attributes that would give Tesla the kind of market dominance that we see with monopolistic companies like Apple or Google in their sectors.

But what Krugman and others miss is the significant technological advantage Tesla has right now over its competitors, in terms of charging speeds and user friendliness of the vehicles (Krugman admits he’s not a “car guy” and so likely hasn’t test driven EVs from different brands before to understand this difference).

But second, and perhaps most importantly, people like Krugman mistake Tesla as just a car company. But it’s not. It’s a fuel station operator, too, with the most significant build out of EV charging infrastructure in the world. What’s more, compared to the competition (third party charging companies rather than other automakers), Tesla’s chargers are higher-powered and more convenient and reliable.

But wait there’s more, as they say on the game shows. Tesla is also an energy storage company, with 152 percent growth last year in its stationary battery business. And it’s a solar roof company, though that latter business has largely been stalled in recent years. So when you package all of these business lines together, you’ll find a vertically integrated monopoly with a significant head start in essentially all of the climate-fighting tech that will dominate the future.

Yes, Tesla stock may be overvalued. But the perception behind it is quite justified. Other automakers need to catch up, as the 2022 sales data reveal, or they will face an existential threat to their survival — much as humans now do, thanks to their gas-guzzling products.

If you follow the press releases of some traditional automakers these days, you might think they are fully committed to an all-electric vehicle future. Since the election of President Biden, companies like General Motors and Ford for example have pledged billions toward electrifying their entire lineup of vehicles.

Yet sales data, company behavior, and policy advocacy reveal a different story. They show a legacy auto industry struggling to compete in a future of all-electric vehicles, with EV products that are falling behind industry-leader Tesla and a generally weak commitment to the needed policies and infrastructure investment.

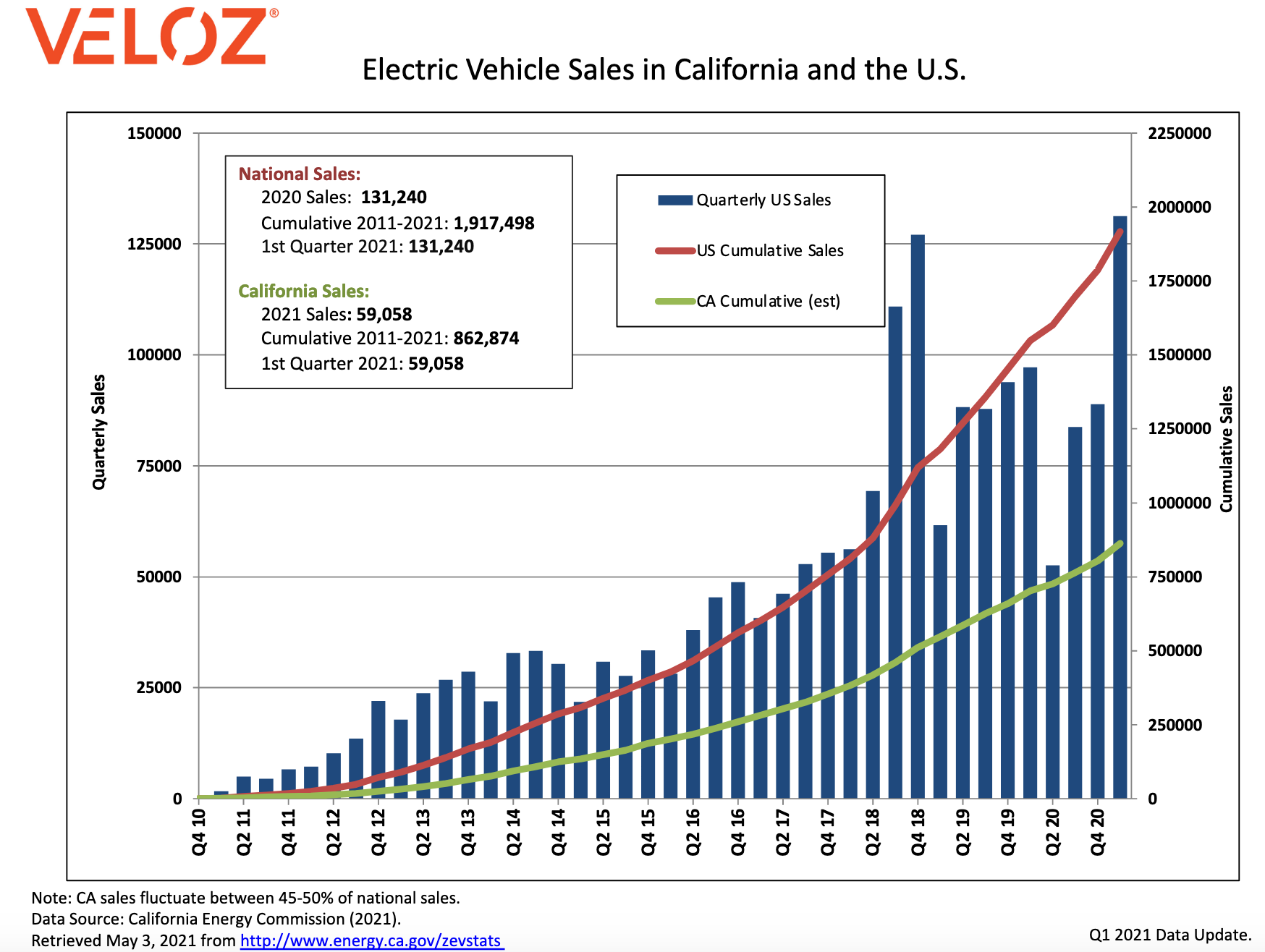

First, look at the sales data. Legacy automakers badly trail Tesla, both in California and nationwide. As a snapshot in California during the first quarter of 2021, as compiled from state agency data by the nonprofit Veloz, Tesla’s Model Y (see photo below) was the top-selling electric vehicle model in the state at 15,265 units sold, with the Model 3 second at 14,536. Next up is the Chevrolet Bolt EV, a vehicle that has remained virtually unimproved since its debut four years ago (though slated to get a minor upgrade this year), at a distant third with 5,252 units sold. The plug-in hybrid (not a true all-electric model) Toyota Prius Prime was fourth at 4,081 sales.

Nationwide, the sales gap is just as stark, according to Car and Driver. The Model Y was again the number one selling EV at 33,629 units in first quarter 2021, more than all other non-Tesla EVs combined. Next was Tesla’s Model 3 at 23,110 units. The Chevy Bolt came in a distant third again at 9,025 units, with the newcomer Ford Mustang Mach-E fourth at 6,614 units sold. Next was Tesla’s Model X at 5,106 (potentially seeing a demand pause ahead of an anticipated update), Audi e-tron and e-tron Sportback at 4,324, and then the Tesla Model S at 4,155 (also ahead of an update and range boost). Notably, the once market-leading EV Nissan Leaf, which like the Bolt has seen little improvement in the decade since it was introduced, clocked in at just 2,925 units sold.

Why are legacy automakers so far behind Tesla in this crucial new technology? Unfortunately, their products and technology are not keeping up with Tesla, though they do tend to have superior reliability and build quality. Most of the traditional automakers’ EV products have shorter range on a single charge, slower charging, and more limited access to EV charging stations. And yet some of these vehicles are actually priced higher than lower-priced Tesla’s, with the companies relying instead on continued access to federal EV tax credits, which have reached their limit for Tesla buyers.

By contrast, Tesla’s leadership had the vision and commitment early on to develop electric vehicle products that consumers want, while investing aggressively in electric vehicle infrastructure and battery and charging technology innovation. For example, Tesla paid for their high-powered Supercharger stations as loss leaders to help sell the vehicles, recognizing that concern over limited access to public charging was a major issue for potential customers. And these Supercharger stations can typically charge the vehicles at a much faster rate than what most non-Tesla EVs can handle.

Despite the press releases on EVs, legacy automakers continue to invest heavily in manufacturing and selling large gas-guzzling SUVs. As General Motors CEO Mary Barra commented recently via Reuters:

Barra added the No. 1 U.S. automaker was focused on maximizing production of high-demand vehicles like the full-sized Chevrolet Silverado pickup, and GMC Yukon, Chevy Suburban and Cadillac Escalade SUVs.

Those polluting trucks and SUVs are a far cry from the all-electric, clean future Barra promises to other audiences. And on infrastructure, these automakers have largely refused to help pay for the charging stations needed to compete in this new field to sell their vehicles, instead relying on third parties and public subsidies.

The companies’ behavior on policy similarly mirrors this weak commitment to EVs. Most if not all traditional automakers have resisted zero emission vehicles policies from the get-go, including fighting California’s landmark zero-emission vehicle mandate from its inception in the 1990s. Up until the most recent presidential election, companies like General Motors and Toyota were eager to side with Trump Administration’s attempted rollbacks of national clean vehicle policy (though notably Ford, Honda, Volkswagen and BMW sided with California). That rollback (now stopped by Biden) would have been a significant setback to the pace of vehicle electrification and climate policy in this country.

But is it all doom and gloom for these companies? Yes and no. Some may now be so far behind on electrification that they might eventually go the way of Kodak and Radio Shack, as hard as it may be to believe now. Others are rapidly trying to pivot and adapt. For example, Volkswagen, after getting caught cheating on its vehicle emissions data, has now been forced to develop new EV product lines, and its new ID 4 crossover vehicle may hold some promise. Other new models, including electric trucks, may also soon prove popular.

But it’s difficult to imagine where the U.S. and the broader electric vehicle industry would be on transportation electrification without Tesla. If not for Tesla, EV sales would be paltry. Legacy companies would likely continue to build the bare-minimum “compliance” cars needed to meet California’s zero-emission vehicle mandate. Automakers would probably still be complaining that EVs are unrealistic, infeasible and not want consumers want. As a result, it would be impossible to meet long-term climate goals, given how much the transportation sector contributes to greenhouse gas emissions.

Fortunately, we’re in a better place now with electric vehicles. Plug-in electric vehicles constituted 9 percent of new car sales in California, the largest EV market in the U.S., with approximately half of nationwide sales (see chart below). It’s decent progress toward a statewide goal of 100% zero-emission vehicles sales by 2035. By comparison, 20% of new car sales in China’s major cities are plug-in vehicles, as Bloomberg reported, with the European Union as a whole at 6.7% market share in 2020, projected to rise to 8.5% this year, per Forbes.

Thanks to this progress, EVs have now broken into the mainstream, providing the credibility to underpin Biden’s new infrastructure plan for boosting them, which includes significant new subsidies and incentives for electric vehicles and charging infrastructure.

But we’ll need many companies to get in on vehicle electrification, including the legacy automakers, both to provide sufficient products for the market and also ensure competition to keep prices low and encourage innovation. At this rate, it’s an open question whether traditional automakers can rebound for the long haul, or if the automakers of the future will instead come from new EV players that follow in Tesla’s footsteps.

Because while the electrification of vehicles is inevitable, the future of the auto industry is decidedly not.

Most trucks on the road today are slow and smelly, causing a majority of the harmful air pollution in urban skies and contributing to our greenhouse gas emission problem. But technology is offering promising solutions to make these trucks zero emission — will they be fueled by battery electric power or hydrogen fuel cells?

Jim Park in Trucking Info lays out the situation with this competition over fuels and technology, and it seems to me that battery power is gaining rapidly. On the hydrogen side, we currently have three main trucking companies: Nikola, Kenworth/Toyota, and a Canadian consortium collaborating on AZETEC (Alberta Zero-Emissions Truck Electrification Collaboration). The battery electric truck side is led right now by Daimler and Tesla.

Hydrogen has two clear advantages over batteries: long-distance range (500-800 miles) with a light payload for the fuel and fuel cell, weighing no more than a typical diesel sleeper tractor. These trucks can also refuel quickly.

But batteries are getting cheaper and more powerful. Electric trucks generally benefit from stop-and-go operations with more opportunities for regenerative braking and high-powered charging. Companies like Daimler are responding to this large part of the market:

“We found that probably 80% of the group we spoke to were not running more than 150 miles per day,” says Andreas Juretzka, head of Daimler’s e-Mobility Group. “That led us to a battery spec of 230-mile range, which covers, among other things, the swings in ambient temperature that can affect battery performance and to alleviate the customers’ range anxiety.”

Tesla has meanwhile announced a 500-mile range truck with zero-to-60 times of less than 5 seconds — sure to be of interest for driving quality alone.

Both types of zero-emission trucks will require a whole new build-out of charging infrastructure though, including fast-charger stations for batteries and hydrogen stations for fuel cells.

This competition over fueling technology is probably good news for consumers and all who live near and drive behind these trucks. But at the same time some clarity on which technologies are suitable for which applications will be needed soon, as policy makers are right now contemplating public investments in the various fueling infrastructure needs. They don’t want to invest in permanent infrastructure for the wrong type of vehicle.

My guess? Battery electrics will dominate for 80% of the trucking market, but hydrogen will still be useful for longer-distance trucking. But either way, the benefits for air quality and our carbon footprint will be immense.

Some heartening recent progress on the EV front, first on consumer demand and automaker supply and second on fast-charging technology:

Some heartening recent progress on the EV front, first on consumer demand and automaker supply and second on fast-charging technology:

- Tesla reported Model 3 third quarter sales of 56,000. They averaged production of 4,300 Model 3s a week, and in the final week of the quarter the company produced 5,300. Perhaps more significantly, the Model 3 had the highest revenue of any car model in the United States, beating out the Toyota Camry and the Honda Accord, which ranked it fifth among all car models sold.

- Major battery maker LG Chem just announced an investment in Enevate, a company that is developing a lithium-ion battery charging technology that could allow EVs to charge at close to the speed of filling up a gas tank. Batteries can get up to 75 percent of their full capacity in just five minutes. With a 200+ mile battery, that means drivers can get 150 miles range in a few minutes.

With lots of gloomy environmental policy news out there, it’s nice to see progress continuing on this crucial clean technology.

As the saying goes, the future is already here, it’s just not widely distributed yet. And when it comes to electric vehicle adoption, infrastructure, and consumer awareness, Palo Alto takes the cake.

As the saying goes, the future is already here, it’s just not widely distributed yet. And when it comes to electric vehicle adoption, infrastructure, and consumer awareness, Palo Alto takes the cake.

As E&E News reported [pay-walled]:

In this city of 67,000, one of the wealthiest in wealthy Silicon Valley, 30 percent of all new cars purchased last year were electric vehicles, according to data from the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT). That’s the highest adoption rate in California, which is home to half of the nation’s EVs. Per capita, Palo Alto is America’s electric car capital.

The affluent community is the home of Stanford and birthplace and bedroom of many major tech companies. Partly as a result of its tech-savvy nature and solidarity with local tech entrepreneur and Tesla CEO Elon Musk, its residents are all in on EVs.

Notably, the city has a tremendous build-out of chargers, particularly at workplaces. Many of the major tech companies have hundreds if not thousands of chargepoints on their campuses.

While not every city in America has the wealth to purchase these sometimes-expensive vehicles and to install all those chargers, as prices continue their steep decline for both infrastructure and vehicles, more of the world will start to look like Palo Alto — at least in terms of its zero-emission vehicle deployment.

I’ll discuss other aspects of EV deployment from this E&E article in two subsequent blog posts.

Lithium ion batteries like those found in electric vehicles have become dramatically cheaper over the past 10 years. But rising demand for cobalt, as well as supply shocks from the Democratic Republic of Congo’s dominant position, threaten this progress. Cobalt prices have doubled since 2016 as a result.

Cobalt samples in Chile

However, we’re now seeing industry respond in two ways. First, mining interests are expanding beyond Congo to address the supply shortage and also diversify the countries holding jurisdiction over the largest deposits. Bloomberg reports that Chile has emerged as a potential site of some rich cobalt deposits, based on some historical research that country’s officials recently did:

Renewed interest in La Cobaltera [Chile] began to emerge last year after Chilean authorities discovered records long buried in the archives of the national geological agency. They showed more than 7 million tons of cobalt ore was mined in the country between 1844 and 1941. The mineral was extracted mainly by German immigrants, who sent it to Europe presumably to manufacture military equipment.

If this discovery holds up, it could provide an important supply source to break Congo’s monopoly, with its human rights and governance concerns.

Second, and more exciting, battery engineers are developing products that require much less cobalt. Utility Dive discussed this trend at Tesla:

In the company’s first quarter 2018 earnings update, Tesla CEO Elon Musk said the company had moved to higher density batteries while reducing the cobalt content of its battery packs. And in June, Musk told shareholders his company would continue to push battery costs down, breaking through the $100/kWh barrier for li-ion cells later this year.

Not only would less cobalt in batteries be a good thing for economic and environmental reasons, it also means prices can continue to decrease. And lower prices mean lower-income car buyers will be able to afford more and better electric vehicles, thereby reducing greenhouse gas emissions from transportation.

These two innovations on cobalt therefore represent promising trends that hopefully will continue for battery production, securing the supply chain for this critical clean technology.

It’s fine if you don’t like Elon Musk. But it’s a mistake to let antipathy for Musk’s ideas, businesses and public persona color your view of electric vehicles, and more specifically Tesla.

And that’s exactly what happens to token “conservative” New York Times opinion writer Bret Stephens. Stephens is otherwise known (at least to me) as a climate skeptic. But in a scathing and highly personal attack on Elon Musk, he betrays ignorance of another subject: electric vehicles.

After comparing Musk to Trump, he makes some misleading charges about Tesla:

Strong words — too strong, if you ask the satisfied customers of Tesla’s Model S (base price, $74,500) and X ($79,500). But Tesla is supposed to be the auto manufacturer of the future, not a bauble maker for the rich.

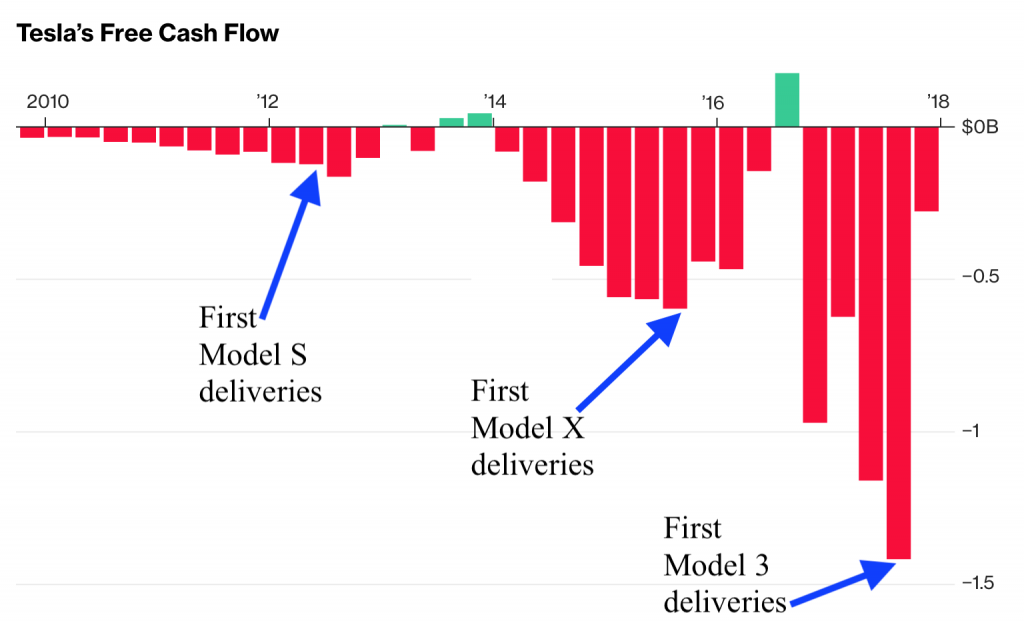

The company has rarely turned a profit in its nearly 15-year existence. Senior executives are fleeing like it’s an exploding Pinto, and the company is in an ugly fight with the National Transportation Safety Board. It burns through cash at a rate of $7,430 a minute, according to Bloomberg. It has failed to meet production targets for its $35,000 Model 3, for which more than 400,000 people have already put down $1,000 deposits, and on which the company’s fortunes largely rest.

Stephens makes Tesla sound like a money-losing luxury automaker. But Tesla could have easily turned a profit a long time ago, if it was in the short-term profit game. But it’s burning cash precisely because it’s scaling up a massive battery, solar panel and mass-market vehicle business. Check out this chart on Tesla cash flow from Ars Technica:

It’s silly for Stephens to take a snapshot of Tesla’s current losses without broader context and insight into the company’s business plan. He whiffs on this score.

It’s silly for Stephens to take a snapshot of Tesla’s current losses without broader context and insight into the company’s business plan. He whiffs on this score.

But it gets worse. He then lobs a broad attack against EVs in general:

Tesla, by contrast, today is a terrible idea with a brilliant leader. The terrible idea is that electric cars are the wave of the future, at least for the mass market. Gasoline has advantages in energy density, cost, infrastructure and transportability that electricity doesn’t and won’t for decades. The brilliance is Musk’s Trump-like ability to get people to believe in him and his preposterous promises. Tesla without Musk would be Oz without the Wizard.

Much of the blame for the Tesla fiasco goes to government, which, in the name of green virtue, decided to subsidize the hobbies of millionaires to the tune of a $7,500 federal tax credit per car sold, along with additional state-based rebates. Would Tesla be a viable company without the subsidies? Doubtful. When Hong Kong got rid of subsidies last year, Tesla sales fell from 2,939 — to zero. It may be unfair to describe Tesla as Solyndra on wheels, but only slightly.

It’s time for fact checks. First, lithium ion batteries and electricity rival gasoline in all categories Stephens mentions. Electricity is ubiquitous (and locally produced). Batteries can recharge in minutes with technology now being introduced on the market, just like a gas station. And cheaper battery packs deliver the range today of a full tank of gas. And on all these fronts, the technology and infrastructure is set to improve in the next few years — not decades, as Stephens suggests.

But even more important, electricity as a fuel doesn’t poison our air and lungs like burning gasoline — or leave us dependent on foreign governments for a global commodity. Gasoline is not priced for those externalities. Since Stephens doesn’t accept climate science, he may not care. But the rest of us should.

And this notion that Tesla survives on government handouts is also misleading. Many Tesla customers are wealthy enough where the tax incentives and rebates don’t factor into their decision-making, according to data collected in California on rebate customers. If anything, Tesla is now hurt by government incentives for fossil fuels and rival automakers with new electric vehicles on the market.

In short, Stephens is ignorant on this topic and unfortunately has written a column that spreads misinformation on a critical climate-fighting technology.

Tesla has been in the news recently for its falling stock prices and corporate troubles. The company’s stock has slid from a high that matched Ford Motor Company, even though Ford sold 64 times the number of vehicles as Tesla last year.

Tesla’s high valuation was based on its projected future market value. Unlike traditional auto companies, Tesla’s vision, if successful, would turn the company into your electric utility, gas station and auto dealer all rolled into one, through separate investments in solar and standalone batteries. Much of the hype was based on the profitability of its supposed first mass-market electric vehicle, the Model 3.

Demand is high for the vehicle, but the company can’t deliver. As Bill Saporito writes in the New York Times:

Tesla can’t seem to run an auto production line, something that the Detroit auto companies that Mr. Musk mocks are very good at. Ford’s electric vehicles and hybrids, such as the Fusion Energi, may not match the Tesla Model X in style or speed, but Ford can knock out millions of fenders and hoods in its stamping operations with absolute certainty and to tight specifications.

Tesla is operating out of the former G.M./Toyota joint venture plant in Fremont, Calif., which produced more than 400,000 cars annually at its peak. Tesla has been running at a quarter of that rate, and has had to resort to pulling cars off the line and finishing them by hand. That’s not what you call mass production; more like mass confusion.

The other problem is that the Model 3 isn’t really a mass-market vehicle. The company is only rolling out the higher-end version, which is priced at about $50,000 before incentives. Who knows if the cheaper version originally promised to consumers will be available at all this year?

Yet as Saporito points out, the global demand for — and investment in — electric vehicles is surging. The market overall is getting stronger, as battery prices fall precipitously.

Whether Tesla can participate in that coming boom will depend not only on its ability to mass produce Model 3s, but to ensure that they are of reliable quality. Otherwise, investor appetite in Tesla will start to wane, particularly as other automakers around the world catch up to the EV vision that Tesla helped pioneer.