As the United States grapples with racism and police brutality in the wake of the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers, environmentalists need not be bystanders in the debate over solutions. Environmentalism has multiple opportunities to help address institutional racism, and few issues cross cut racism and environmentalism more than housing policy.

Environmentally, housing policy that encourages urban development is crucial to reducing emissions from automobiles through decreased commute times and car dependency, as well as limiting development pressure on open space and agricultural land. And from a racial and economic justice perspective, more inclusive housing policy is vital to undoing pervasive residential segregation in America today.

While the Civil Rights movement and the resulting laws helped make explicit racism illegal in housing, predominantly white local governments and their allies can still legally practice housing racism through restrictive local zoning and permitting processes. As Michael C. Lens and Paavo Monkkonen from UCLA’s Luskin School of Public Affairs documented in a recent study, local restrictions on housing density and complex housing approval processes are highly correlated with wealthy residents walling themselves off from those with diverse incomes and of different races. And the more hands-off a state government is on housing policy in favor of “local control,” the more segregated the state will be.

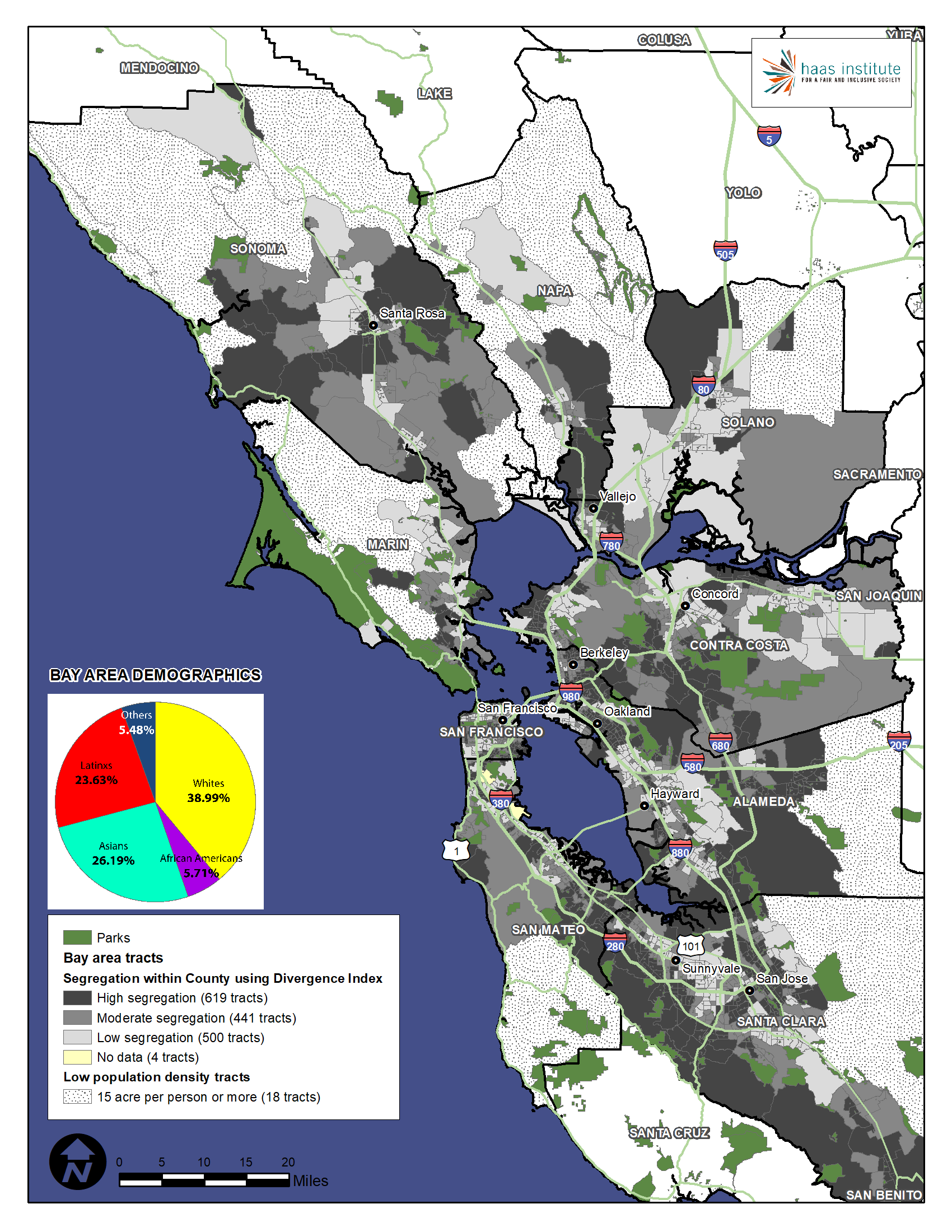

You can see this dynamic in stark terms in the San Francisco Bay Area. UC Berkeley researchers Stephen Menendian and Samir Gambhir comprehensively mapped racial demographics throughout the region, and found that whites are the most segregated racial group in the region. Although whites are just under 40 percent of the Bay Area’s population, 184 of 1582 census tracts are more than 75 percent white, with 359 tracts more than 66 percent white and 663 tracts more than 50 percent white (see map below). Contra Costa County alone in the East Bay features some of the most racially segregated white neighborhoods in the entire Bay Area: Walnut Creek (63 percent white) and Martinez (69 percent white), with Lafayette at 77 percent white (a city that was a recent New York Times poster child for exclusionary local land use policies).

The Los Angeles metro area fared no better, as the 10th most segregated metropolitan area in the country, according to one index.

So what can be done to address this fundamental form of racial segregation? Simply put, the state and federal government need to intervene to ensure that local governments cannot practice racially and economically exclusionary local zoning. By limiting the number of apartment buildings and affordable homes that are built in their communities, high-income whites are limiting racial diversity in their communities, while sending a message to people of color with incomes to afford to live in these areas that they are not welcome.

Earlier this year, the California State Senate debated a bill (SB 50 by Sen. Wiener) that would have accomplished just that: making it illegal for high-income areas to prevent apartment buildings and affordable homes near major transit. Yet a majority of state senators — many from these segregated, high-income areas, including Contra Costa, Malibu, West LA, and Silicon Valley — voted against it.

If Black Lives Matter, then surely black neighbors should too. California, like many other states around this nation, needs to address this root cause of segregation — to achieve outcomes of both environmental sustainability and racial justice.

With the COVID-19 virus shutting down cities and countries all over the world, anti-urban advocates are seizing the moment to argue that pandemics prove density is bad. For example, longtime sprawl booster Joel Kotkin argues that shelter-in-place orders and fear of contagion will push people to demand more lower-density homes, far from crowded and ailing cities.

These advocates have some support from scientists. Some public health experts point to density as a factor in spreading the disease, as the New York Times recently reported:

“Density is really an enemy in a situation like this,” said Dr. Steven Goodman, an epidemiologist at Stanford University. “With large population centers, where people are interacting with more people all the time, that’s where it’s going to spread the fastest.”

But at the same time, some of the densest nations around the world have had the most success fighting the spread of the virus, such as Taiwan, Japan, Korea, and Singapore. In particular, Taipei and Saigon city leaders (among others) have been extremely effective in controlling the contagion.

By contrast, low-density suburbs have been among the first sites where the virus took hold in the U.S., such as in Kirkland, Washington, and New Rochelle, New York. Similarly, the outbreak in Italy began in small towns outside of Milan.

Given this evidence to date, governance appears to be far more important a factor than density in limiting the spread of the virus. Furthermore, density could actually be more helpful in controlling the spread, as governments can more easily enforce sheltering in place in smaller zones, while emergency response times and trips to the hospitals are typically faster than in far-flung rural areas (which also suffer a dearth of available medical facilities, as my colleague Dan Farber pointed out).

But the question remains: could the pandemic dampen demand for housing in dense urban environments, regardless of the science? People may still (perhaps irrationally) fear a dense environment as a disease-spreader. Or they may emerge scarred from this era of “sheltering in place” and prefer larger homes with outdoor space, just in case another pandemic requires a new round of society-wide house arrest.

History may provide some guide in answering this question, as low-density homes in the 1920s were certainly sold to the public as antidotes to disease-ridden, crowded cities. As Emily Badger noted in the New York Times, “[r]espiratory diseases in the early 20th century encouraged city dwellers to prize light and air, and something that looked more like country living.”

But as policy makers weigh options to boost density, they should keep in mind the myriad public health benefits that density can provide. It can foster more physical fitness from increased walking and biking instead of sedentary, automobile-based sprawl; mental health benefits from strong and frequent community interactions; and stronger health care from pooling resources for big public hospitals.

Furthermore, in an era of climate change, living in more compact environments can guard against extreme weather events. In California, for example, urban neighborhoods are among the most fire-safe during destructive and worsening wildfires, while also largely avoiding the electricity shut-offs needed to avoid igniting fires in high-fire sprawl zones. From a public safety perspective, density can now save lives during wildfires.

And sheltering in place in a more compact environment can bring elements of joy and community during a time that can otherwise feature crushing physical and emotional isolation. Witness scenes of a balcony opera performance in Florence to help neighbors cope with the lockdown or police in Mallorca, Spain singing songs for neighbors while enforcing the quarantine.

The human connection found in dense neighborhoods can not only help us get through this particular challenging time in human history, it can build the foundations for a healthier, more sustainable future. The current pandemic won’t change that reality.

Sen. Scott Wiener is back trying to boost California housing production again, after his SB 50 legislation to upzone for apartments around transit died in the State Senate in January. This time, he’s proposing a “lighter touch” approach, salvaging an SB 50 provision that would end single-family zoning across the state.

Senate Bill 902 would authorize minimum residential zoning of duplexes in unincorporated county areas or cities under 10,000 residents. Triplexes would be the minimum density for cities between 10,000 and 50,000 residents, while fourplexes would be allowed for cities of 50,000 or more.

Furthermore, while local standards on height, setbacks, and fees, etc. would remain in place, any approval for these multiplexes would be “by right,” meaning environmental review would not apply under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) and permits would not be discretionary. In addition, the bill would not apply to parcels with renters any time in the last seven years, historic structures, or high-fire zones.

But wait, there’s more — and this time with a more explicit transit and environmental hook.

SB 902 would also allow local governments the option of rezoning any parcel (including for commercial uses) for up to 10 units in density, provided the parcel is located in a “transit-rich area, a jobs-rich area, or an urban infill site.” The definition of transit-rich means within one-half mile of any rail station or major bus stop, and urban infill site essentially means a previously developed spot surrounded by existing uses on at least 3 or 4 sides. “Jobs-rich” would need to be defined by the state’s planning and housing agencies. Like the multiplex provision, all permitting for these 10-unit parcels would be by-right and therefore not subject to CEQA.

This 10-unit opt-in provision holds the most promise to boost transit ridership and reduce vehicle miles traveled (aka “traffic”), the reason the state is now falling behind on transportation emissions. By allowing an opt-in for greater density, SB 902 provides off-the-shelf tools for local governments that actually want to see more housing near transit and jobs.

That said, the problem in California is that too many transit-rich, high-income local communities want nothing to do with more density. So many of the most critical transit-rich communities (San Francisco Bay Area suburbs and Westside Los Angeles cities like Beverly Hills) likely won’t budge on this tool. Their property-rich residents are just fine with their neighborhoods as they are.

The upside for the environment on the multiplex provision is that accommodating more residents in existing residential neighborhoods could also boost transit, if those new multiplexes are near rail stations and bus stops. And if those new residents drive, at least they would presumably have a shorter commute than if they lived in new exurban sprawl communities (the primary affordable housing alternative, short of leaving the state altogether).

The potential downside is that many of these multiplexes might be in far-flung subdivisions, meaning the new residents will have longer commutes than if SB 50 had passed and they could have lived in an apartment near transit. But the SB 50 opportunity, and all the mandatory affordable housing that would have come with it, is now passed.

As for the politics on SB 902, it seems likely it will be similar to SB 50. Wealthy suburbanites that sank SB 50 will be back en masse to oppose SB 902. Labor may not like the by-right provision (they use CEQA to force project labor agreements on developers) but may appreciate the construction jobs.

The political wildcard will be equity and affordable housing groups, which helped sink SB 50. Will they care about suburban upzoning? Some of these affected areas will have low-income tenants. While as mentioned the bill doesn’t allow redevelopment with renters present anytime in the last seven years, many tenant advocates may not care. Some are even hostile to market-rate development of any type, hoping instead for a government takeover of housing production. So it will be critical to see what positions they take on SB 902, as their opposition to SB 50 provided important political cover for wealthy opponents.

In addition, will environmental groups step up to support the measure? Most were MIA on SB 50, with the exception of NRDC, ClimateResolve and a few others. Some were even opposed, cowed by the tenant group opposition or beholden to NIMBY constituents. So SB 902 gives them a fresh opportunity to finally develop a coherent position on this most pressing environmental issue.

Ultimately, if Sen. Wiener can at least limit tenant group opposition, along with the wealthy NIMBYs who may be more scandalized by the prospect of an apartment building than a triplex, he may have a chance to get the bill passed. And ultimately, it will require the governor, who campaigned on 3.5 million new housing units but has instead seen backwards progress, to step up and get more involved in the political process.

Either way, if the bill has legs, we’ll likely see many changes as it winds its way through the process of political compromise. I’ll be following them closely.

California (and the nation as a whole) is getting worse in our efforts to reduce emissions from transportation (i.e. driving). Last week, I gave a talk in the UC Berkeley Institute of Transportation Studies lecture series on what we can do about it. You can view the recording here:

In brief, we’re failing because driving miles are up while transit usage is down, in part due to poor land use policies that pushing housing farther from jobs. We need to encourage housing near transit and encourage electric vehicle usage for all other driving.

And on the subject of how we’re failing to build enough housing near transit, you can view a recording of a January 30th symposium at UC Hastings School of Law on this topic, featuring two panel discussions (I spoke on the second) and a closing keynote from State Senator Scott Wiener. You can also read a summary of the symposium from Hastings student Leigha Beckman, who helped organize the event.

Happy viewing!

The California State Senate this morning (for a second time after an initial vote last night) narrowly and finally killed SB 50, a major climate-land use bill that would have allowed apartment buildings near major transit stops and job centers. Despite high-profile opposition from some low-income tenants groups, the senators voting against the bill largely represent affluent suburbs.

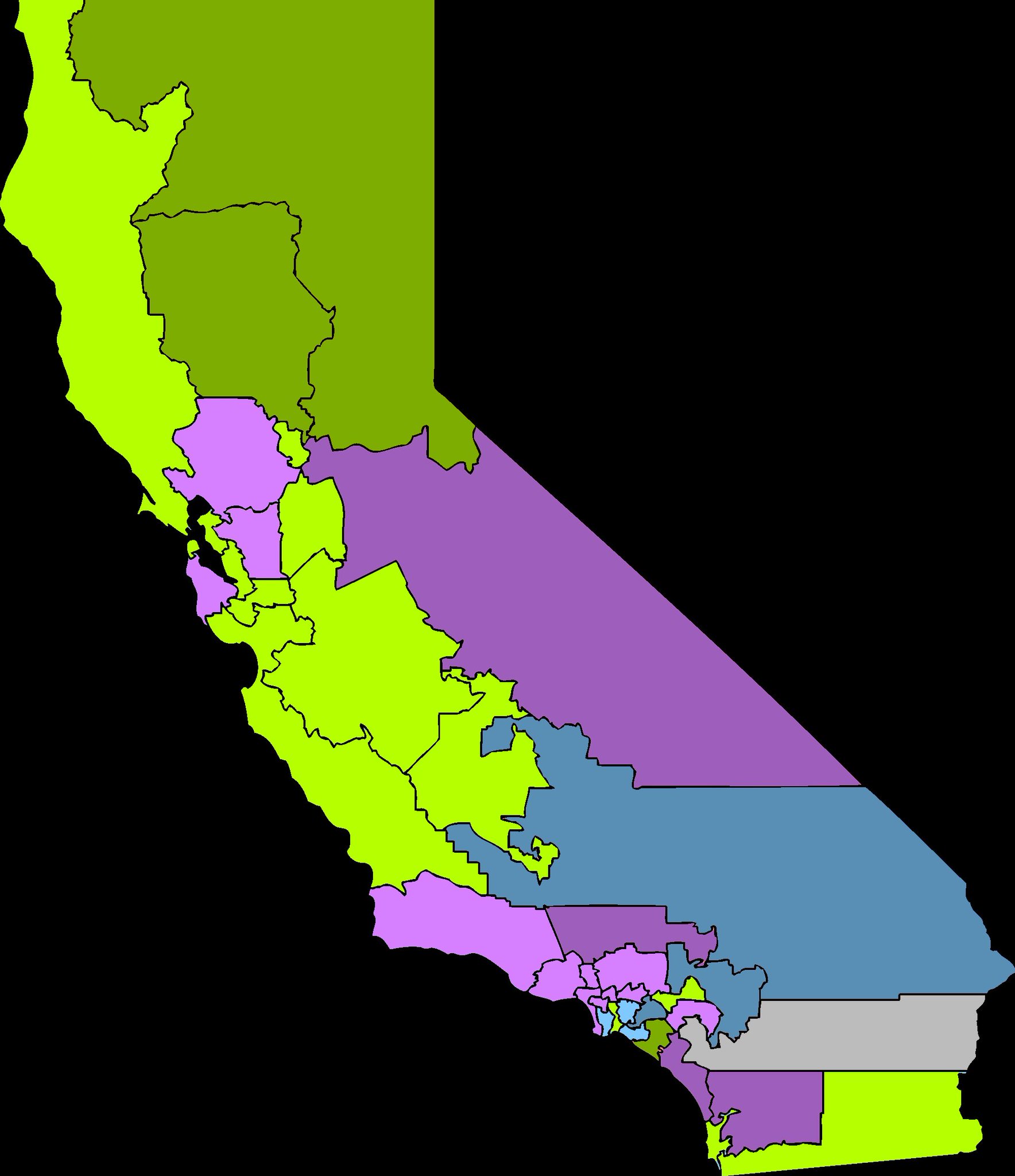

To illustrate the geographical divide, a Twitter user put together this map of the senate districts and votes, with purple opposed, green in support (light for Democrat and dark for Republican), and blue abstaining:

As you can see, the “opposed” senators largely cluster along on the affluent coastal and suburban areas. This dynamic is particularly apparent in the San Francisco Bay Area, where representatives of the urban core supported the bill (including bill author Sen. Scott Wiener and Sen. Nancy Skinner). But the senators representing the suburban, high-income Silicon Valley communities (Sen. Jerry Hill), affluent East Bay suburbs (Sen. Steve Glazer), and the Napa area (Sen. Bill Dodd) were all opposed.

Meanwhile, Southern California Democrats representing high-income coastal suburbs were almost uniformly opposed:

- Sen. Hannah-Beth Jackson, representing Santa Barbara communities;

- Sen. Henry Stern, representing Malibu and suburbs north of urban Los Angeles;

- Sen. Ben Allen, representing the Westside of Los Angeles, including Manhattan Beach and Beverly Hills;

- Sen. Anthony Portantino, representing La Cañada Flintridge and who had unilaterally shelved the bill last year in his committee; and

- Sen. Bob Hertzberg, representing the San Fernando Valley.

Notably, there were some standout “profiles in courage” votes in favor of the bill, including:

- Sen. Lena Gonzalez from Long Beach, despite opposition from city leaders in her district;

- Sen. Brian Dahle from the conservative, northern inland part of the state, who recognized the damage sprawl does to farmland;

- Sen. Bill Monning of Carmel who spoke passionately about the inequality and devastating commutes wrought by exclusive local land use policies; and

- Sen. John Moorlach of coastal Orange County, a Republican (and bill co-author) who appreciated the legislation giving more property rights to landowners.

What were the argument of opponents? They largely involved these issues:

“The bill will not produce enough affordable housing.” The bill in fact contained minimum requirements that projects receiving benefits under the bill include affordable units. As a result, SB 50-type reform would result in the biggest boost to subsidized affordable units in the state’s history, at possibly a seven-fold increase.

“SB 50 takes away local control.” To the contrary, the bill would give low-income communities five years to develop local plans for infill housing and two years for other communities to plan to meet these standards. Locals would be free to set more aggressive standards on affordability and relax restrictions even more if they wanted to do so. SB 50 also did not alter local permit approval processes. Furthermore, for senators who profess to care about the housing shortage, local control is the single biggest cause of the shortage, particularly through restrictive zoning.

“The bill will lead to gentrification and displacement.” This is a real, yet overstated, concern that the bill addressed with numerous provisions to protect against new developments displacing low-income tenants (a massive, ongoing problem that predates SB 50 and is made worse by the exclusionary housing policies SB 50 was designed to prevent). Furthermore, local governments were free to go beyond those protections. Second, as UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation documented, any projects under the bill only “pencil” in high-income areas where developers get higher returns. Finally, as the Urban Displacement Project at UC Berkeley (in collaboration with researchers at UCLA and Portland State) found, new market-rate and affordable housing at a regional scale reduces gentrification and displacement overall.

Finally, Sen. Henry Stern uniquely argued against the bill for encouraging development in high-fire zones. It was an odd argument, considering that the SB 50 zones around transit are in some of the only non-fire, urban zones in the state, while the bill contained explicit language preventing application in high-severity zones. Furthermore, encouraging growth in infill areas reduces pressure to sprawl into the same wildlands Sen. Stern is worried about. Yet Sen. Stern was convinced that the protections weren’t strong enough and conceivably was worried that the provision in the bill allowing conversion of single-family homes into fourplexes would put more people into harms way. Given this logic, will Sen. Stern now support a bill banning new construction in high-fire zones? Or would he have supported the bill with an amendment banning such construction? He did not respond to these questions on his Facebook page.

So what’s next? The bill or some form of it could be brought back this legislative session as a “gut-and-amend” of an existing bill. Indeed, Senate pro tem Toni Atkins vowed shortly after the vote to bring a housing production bill back before the legislature this session. Supporters could also try a more limited approach, such as exempting controversial parts of the state from the bill.

Otherwise, given the long-term problem and entrenched opposition to change, the fact that such a landmark bill only fell three votes short is quite an accomplishment. Since the problem will only get worse, the political pressure to act will increase. That means that something like SB 50 will ultimately pass in California. It will be too late for those priced out in the near term, and possibly too late to address our 2030 climate goals, which will require reduced driving miles from housing closer to jobs and transit absent major technological innovation. But it will happen, because reforming our land use governance is the only way to solve this problem.

Bay Area legislators State Senator Scott Wiener (San Francisco) and Assemblywoman Buffy Wicks (Berkeley) will discuss housing legislation with me tonight on City Visions at 7pm, on 91.7 FM KALW in San Francisco.

Governor Newsom wants 3.5 million new homes built by 2025. How are our legislators planning to get us there? We’ll discuss Senator Wiener’s revamped Senate Bill 50, which encourages development around transit and job centers. And we’ll also find out Assemblywoman Wicks’ plans for this year, after she introduced a suite of housing legislation last year.

Tune in and ask your questions at 866-798-TALK! We’ll be streaming live at 7pm.

As the debate over SB 50 and other state legislative efforts to boost California’s housing supply heats up, it’s worth reviewing some of the data about how dire the housing situation is in the state. Here are some tidbits:

High Home Prices and Rents:

- According to the California Legislature’s Legislative Analysts Office, the average California home costs about two-and-a-half times the average national home price, at $440,000 (and much higher in major metro areas). This price divergence began in the 1970s, when California home prices went from 30 percent above U.S. levels in 1970 to more than 80 percent higher by 1980.

- Per the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD), the majority of California renters (more than 3 million households) pay more than 30 percent of their income toward rent, while nearly one-third (more than 1.5 million households) pay more than 50 percent of their income toward rent.

- Per a Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice study, 19% of community college students in California are homeless, while 60% are considered “housing insecure.”

- Almost one-quarter of all homeless people in the country live in California, according to federal data.

Extreme Housing Shortage Relative to Demand:

- California ranks 49th among all U.S. states in housing units per resident, behind only Utah, where residents tend to have large families in single homes, per a 2016 McKinsey study. The McKinsey analysis showed that California has 358 homes per 1,000 people, whiles comparable states like New York and New Jersey have more than 400 homes per 1,000 residents.

- HCD calculated that the state needs to build 180,000 additional homes annually, but over the last ten years housing production has averaged fewer than 80,000 new homes each year (and is currently declining).

Local Zoning is a Key Barrier:

- While the 2016 McKinsey study presented a goal of 3.5 million units needed to address the shortage and stabilize prices, UCLA’s Lewis Center found that California cities and counties currently only zone for a combined 2.8 million new housing units. And many of these zoned parcels are located in rural areas far from jobs, which is not where housing is needed.

- The New York Times recently mapped the local zoning in some major cities and found that 75 percent of Los Angeles and 94 percent of San Jose is zoned exclusively for single-family homes.

- UC Berkeley’s Terner Center documented via a statewide survey of local governments that in two-thirds of California’s cities and counties, multifamily housing (i.e. apartments) is allowed only on less than 25 percent of the available land.

- The Terner Center similarly showed that fully one-half to two-thirds of all land in California is reserved exclusively for single family homes.

- In 1933, according to University of Texas’s Andrew Whittemore, less than 5 percent of Los Angeles’ zoned land was restricted exclusively restricted for single-family homes. By 1970 though, half of the land in Los Angeles was zoned only for single family residences, per UCLA’s Greg Morrow.

- Morrow noted that zoning in Los Angeles went from allowing up to 10 million residents in 1960 to 3.9 million residents by 1990.

Local Permitting Processes Remain a Major Barrier:

- The Terner Center estimated that local permit and impact fees on new units average $150,000 per unit.

- Environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), triggered when local governments make permitting decisions discretionary as opposed to ministerial, ranked as the ninth biggest barrier to housing overall, according to the Terner Center survey of planners.

- The Rose Foundation found that CEQA litigation affects fewer than 1 out of 100 projects not already exempt from the law, while litigation has been steady at about 195 lawsuits per year on average since 2002.

These numbers on California’s housing crisis show not only the human cost of the shortage, but the need for a strong policy response to fix the governance system that exacerbates the problem. We’ll see if this legislative session brings any change.

The UN climate conference in Madrid last month may have ended poorly, but conference attendees had a big success story right in front of them. Spain’s success achieving efficient – and enjoyable – land use and transportation outcomes is a model other countries and states should emulate to address climate change.

Spanish cities and towns feature many remarkable urban spaces, not unlike those found in other European countries. These areas tend to prioritize compact apartments located within walking distance of abundant transit, shops, bike lanes and jobs, with many containing pre-automobile-era narrow cobblestone streets built for people and not vehicles. Cities are often built around plazas, typically along with town halls and churches. They also protect against sprawl by prioritizing open space and agricultural land, particularly in the central and southern part of the country. Meanwhile, a high speed rail network connects most of the country’s major urban areas.

The result? While many factors probably come into play, US News in 2019 ranked Spain tops among all countries in terms of the overall happiness of its citizens. The country also ranked 18th in overall quality of life and among the top in food and culture.

You can see this effect on the ground. Spanish cities and towns are among the most walkable and enjoyable cities I’ve experienced. Particularly in the capital city of Madrid, where the UN conference was held, residents can access most destinations by transit or on foot, and the central city is closed to vehicles not registered to central city residents, while any other entering vehicle must meet low- or zero-emission standards. As a result, the Madrid city center is a quiet and clean pedestrian playground. And this same dynamic is present in cities and towns throughout the country, based on my travels there. It’s likely a major reason for the country’s success in terms of emotional well being.

This urban walkability has positive environmental effects, too, particularly on greenhouse gases. According to World Bank figures, Spain’s per capita carbon emissions is 5 metric tons, ranking it approximately 60th on the list of 192 countries, despite having a GDP per capita that ranks roughly 30th. These emission figures stand in stark contrast to the 16.5 metric tons of emissions for the average United States resident, more than 3 times as much as the average Spaniard. And even similarly developed and urban countries like Japan and Germany have almost twice the emissions per capita of the Spanish, with 9.5 per Japanese resident and 8.9 per the average German.

To be sure, some of this climate progress is due to their increasingly clean electricity grid, which has seen a significant deployment of renewables over the past decade. But smaller homes and walkability that decreases driving miles helps, too. For example, overall driving miles (or kilometers, in this case) in the country is relatively low for a developed nation, at approximately 400 billion per year. With 47 million residents in Spain, that equals roughly 8,500 km per person, or 5,287 miles per year (14.5 miles per day per person). By contrast, according to the Eno Center, the average Californian drives 50% more miles than the average Spaniard, at 8,728 miles per year, or 24 miles per day (rural states do even worse, with Wyoming at a whopping 16,900 miles per year, or 46 miles per day per person).

The lessons learned? Policy makers should design towns to maximize walkability and transit access, limit private vehicles, prioritize public spaces like plazas, and preserve surrounding farmland and open space from sprawl. Hopefully attendees at the UN Climate Conference experienced some of these Spanish practices on land use and transportation firsthand. Because the climate-friendly results mean cleaner and happier living overall, something worth achieving everywhere.

California State Senator Scott Wiener launched his third legislative attempt today at boosting California’s housing supply. SB 50 aims to address the state’s massive housing shortage, which has resulted in high home prices and rents, gentrification, displacement, inequality, homelessness, and a mass middle-class exodus to high-emission states like Texas and Arizona.

Because this housing undersupply is caused primarily by restrictive local land use policies in the state’s coastal job centers, Wiener’s approach has been to require cities and counties to allow apartment buildings near major transit centers. His first attempt in 2018 (SB 827) died quickly in committee. His second attempt last year (the birth of SB 50) was unilaterally shelved for a year by State Senator Anthony Portantino, who represents the affluent Southern California city La Cañada Flintridge (that city quickly became a poster child to housing advocates for high income single-family homeowners who don’t want to allow new residents in apartments into their neighborhoods).

The clock is now ticking on SB 50 in 2020. Under legislative rules, the bill must pass the full Senate by the end of this month — and first make it out of Sen. Portantino’s committee.

So Sen. Wiener is trying again, unveiling at an Oakland press conference this morning a critical amendment to delay statewide implementation for two years in order to give local governments the opportunity to develop their own plans that meet or exceed the housing, equity and environmental goals of SB 50. Otherwise, SB 50’s provisions relaxing height, parking and density requirements around major transit stations will automatically prevail.

Specifically, the state (through the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research) will develop guidance for these “local flexibility plans” by mid-2021. Cities and counties must then submit their plans for approval to the California’s Department of Housing and Community Development. That agency will then certify that the local plans are as stringent as SB 50. The local plans must be in place by January 1, 2023 in order to avoid defaulting to SB 50 statewide standards.

Otherwise, the substance of the bill remains essentially unchanged from last spring (here’s my rundown on the last changes before Sen. Portantino shelved it).

These new amendments seek to mollify critics who complained that the statewide approach undercuts local flexibility to meet the targets in a more tailored way. For example, rather than having uniform four-story apartment buildings around a major transit stop, perhaps a city would prefer to meet the overall housing production goals with a taller building in one spot and a shorter building across the street.

Will these changes be enough to satisfy local government objections? Probably not in many cases. The objections are less about local control and more about visceral dislike for apartment buildings and the residents they may bring. Arguments about local control — and relatedly against market-rate housing and instead building only subsidized affordable units — are often not made in good faith. Critics quickly move the goal posts as soon as amendments are made in their direction.

Take for example Sen. Portantino’s initial reaction to these amendments, complaining about not enough affordable housing, per his spokesperson to the San Francisco Chronicle:

“It was the senator’s hope that by taking a breath with SB50 it would focus efforts on actually building affordable housing as opposed to the market-rate housing predominant with SB50.”

This comment ignores that SB 50-type reform would result in the biggest boost to subsidized affordable units in the state’s history, at possibly a seven-fold increase. All without raising taxes or issuing bonds, and without delay about where to build these units even if public funds are available.

Still, these amendments may persuade critics who are on the fence. And perhaps most critically: will Governor Newsom now throw his weight behind the measure to help it pass? This is a big test for the governor on one of his signature campaign issues.

All in all, the next few weeks will be instructive as to whether or not California leadership can meaningfully address the the housing shortage and its severe equity, economic and environmental consequences.

UC Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) is today releasing a new report on lessons learned to advance electric vehicle (EV) deployment in France and California. Electric Vehicles and Global Urban Adoption: Policy Solutions from France and California is based on a June 2019 international conference at UC Berkeley, co-sponsored by CentraleSupélec and Florence School of Regulation (FSR) in France, featuring speakers from California and French utilities, energy regulators and industry.

Electric vehicles are important to both California and France because transportation accounts for approximately 20 percent of emissions in Europe, 30 percent in the United States, and 40 percent in California (and even more when factoring in emissions from oil refineries). Yet electric vehicles still represent a small share of the overall vehicle market worldwide, at under 10 percent of new car sales in California and under 2 percent in France, despite aggressive policy targets.

Deployment in California and France is more perhaps more complicated than other jurisdictions, given that approximately 40 percent of residents in both places live in multi-unit dwellings, such as apartments, townhouses, and condominiums. Many of these dwellings are in urban areas with little or no access to charging, given the lack of dedicated parking spots and lower vehicle ownership rates. French law requires builders of new apartment buildings to install chargers, but residents of existing buildings don’t receive those benefits.

As leaders in California and France seek to boost EV adoption, speakers at the conference identified the following challenges, also summarized in the report:

- Lack of access to affordable, convenient private electric vehicles;

- Complexity and cost of installing charging in urban settings and existing multifamily buildings;

- Declining federal incentives and insufficient vehicle demand;

- Electricity rate design decreases the financial viability of charging stations;

- Difficulty of adopting optimal charging practices that could benefit users and electric utilities;

- Difficulty of adopting optimal charging practices that could benefit users and electric utilities; and

- Need for grid infrastructure upgrades to avoid high costs on first-movers.

The conference speakers also discussed priority solutions, as the report details, including:

- National and state governments could require owners of existing multifamily buildings to install charging stations;

- National and state governments could assist transportation network companies (TNCs) like Uber and Lyft in encouraging electric vehicle adoption among their drivers, through support for the deployment of fast-charging hubs, driver education programs, and new pilot projects; and

- Electric utilities and regulators could develop new rate designs to incentivize charging while optimizing grid efficiency.

These and other solutions are discussed in the report, which will hopefully help stakeholders in both jurisdictions achieve an electric future for transportation. Bonne route!